In this issue of CuraLink, we speak with Dr. BJ Miller, a physician leading a revolution in hospice and palliative care. Our powerful discussion covers daring territory around the way we die and the failures of a “fix everything” medical system. The conversation should be helpful for anyone navigating a health challenge, caring for a loved one in their final days or treating patients.

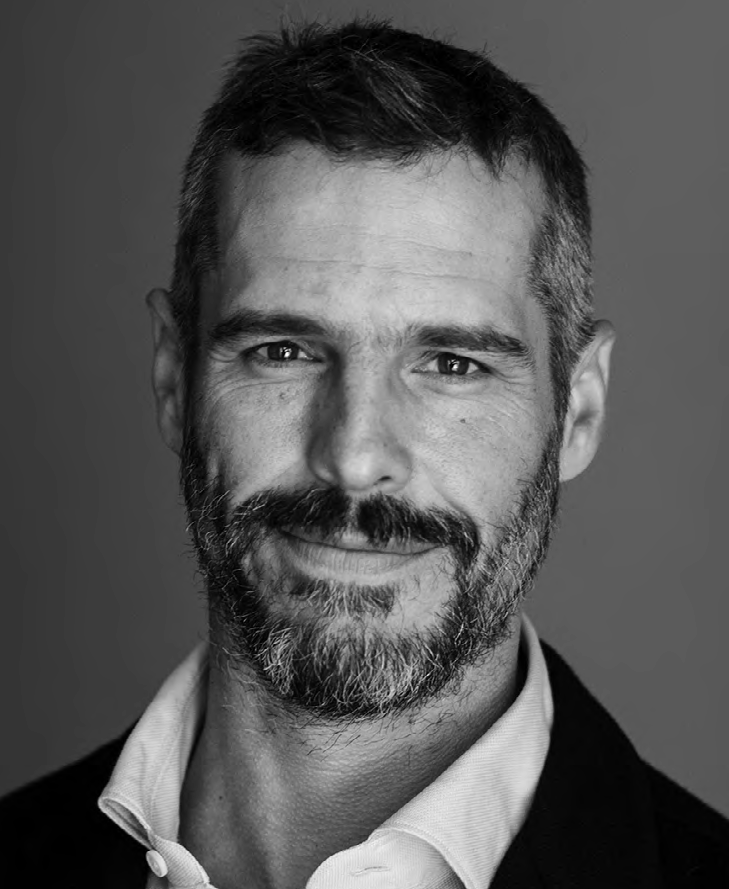

A conversation with Dr. BJ Miller

While much of health care revolves around fixing problems or treating disease, the specialty known as hospice and palliative care has another goal: support people’s quality of life and provide comfort, dignity and assistance to the dying or those with serious illnesses.

According to Dr. BJ Miller, one of the leading specialists in the field, this approach is surprisingly rare. That’s because medicine is hyperfixated on acute, life-preserving care, which can improve short-term outcomes but can also breed unnecessary suffering. It’s a “fix on a fix on a fix,” Dr. Miller says, without asking patients what they really want or need.

We need to have more resources to support and guide families in the face of healthcare challenges including end-of-life care. Dr. Miller feels that we wait too long to surround people with loving attention when they need it the most. We’re long overdue for a comprehensive overhaul of the healthcare system and a total rethink around death and disease.

You had an experience early in life where you came close to death that shaped your career. Will you share the story?

When I was 19 and in college, I was horsing around on top of a commuter train one day. I had a metal watch on my left wrist, and when I stood up on top of the train, the electricity from the cables overhead arced to the watch. That was it. I got large electrical burns and nearly died. I ultimately lost my left arm below the elbow and both legs below the knees, but I survived.

BJ Miller, MD, Co-Founder, Mettle Health

How did this experience change the way you think about death?

At 19, I was aware that we all die. We all know that fact, intellectually, but knowing that in your bones and feeling life hanging by a thread—that was new to me. Experiencing that feeling was powerful—it opened me up, helped me sense the connections between me and everything else and how much I needed people to help me survive. It gave me a more nuanced appreciation for life and others.

This experience helped me see the world beyond intellectual and cerebral orientations. I wanted to learn from the experience and let it shape me—not just overcome it or put it behind me as some people would suggest that we do with a negative experience or disability. No, the experience was too fertile and rich, I decided to use it as grist, as a sort of nucleus to grow from.

Why choose medicine and specialize in hospice and palliative care?

Medicine saved my life. It is amazing what humans can do in the name of medicine. I felt some indebtedness to the field. But I was also aware of the weaknesses of our medical model. I found it fascinating.

To be honest, a career in medicine also seemed like a very high bar at that stage in my recovery, but it motivated me. When you’re living with illness or disability, you see how the world reacts to you and treats you. The pity stuff can diminish your sense of self. If you take the bait of being special, you also take the bait that removes you from the flow of normal life and pulls you to the side.

At that point, the world didn’t expect much of me except for maybe that I could get to the bathroom and back. I had a pass. It was appealing to me not to take it and choose something more extraordinary.

During your recovery, did you notice gaps or opportunities for improving this field of medicine?

From the beginning, it was so clear that besides medical technique and technology, it was in the relationships where healing happened. Not just with my doctors, but the nurses and, perhaps most poignantly, the burn techs, who have the ridiculously difficult job of debriding burns—causing so much pain to help someone survive. But relationships are afterthoughts in medicine, and it was very obvious to me that this was a problem. Medicine is not set up to honor relationships.

Another issue was our fixation on curing and fixing folks. Fixing things is beautiful, when it’s possible. The problem is that it’s not always possible. For everybody, eventually, it’s impossible. If you solely focus on fixing someone, you will abandon them when they’re no longer fixable. I have watched that as someone who lives with disability—something that wasn’t fixable in a way.

I watched how my dynamic with others changed as I moved through the healthcare system. Sometimes, I got second-class treatment, and people would avoid eye contact. I became an object and almost a projection of shame and failing. That is a terrible banner to operate under.

It became clear that beauty as a therapeutic mode is dramatically underappreciated in the medical world. I don’t mean prettiness, but beauty like truth incarnate, the environment of care, how we treat each other and tend to our physical settings. That aesthetic domain was very attractive to me. I wanted to help make that a part of normal care.

You’ve counseled thousands of people at the end of life. What do the dying teach us about living?

First, there’s a great book by Frank Ostaseski called The Five Invitations. One of my favorite ideas that Frank mentions is: welcome everything and push away nothing.

Dr. Miller during his recovery from his near-death experience in January 1991 that influenced his choice to become a doctor and a hospice and palliative care specialist

Many of us move through life with a version of loving life that is very critical. We say: “I’ll love life if this happens,” or “I’ll love myself if I do these things.” We place lines between good and bad stuff, things we want or hate. But then you watch someone in a cascade of loss with everything falling away. Everything must go, even the parts of themselves they wish had been different. When it’s about to go, people realize they kind of love that stuff, too.

So one big lesson is to aim for a more expansive idea of love, one that does not pick and choose or hold love hostage. A corollary of that would be to craft our views of ourselves in the world that includes every piece of us. It’s like intrapersonal DEI (i.e., diversity, equity and inclusion)—welcoming every nook and cranny of your experience. That is a big, beautiful lesson that I see happen when people die. It’s not a choice. It’s because you have to say goodbye to everything. You realize that even pain has its place. Even the parts of you that you hated have a place.

We should also cultivate a more expansive notion of life that includes death. The rest of us, who are often unwashed by this stuff, buy into this idea that life and death are opposed. That’s a heavily reduced notion of reality. Nature shows us this constantly, but we just ignore it. We are all living and dying at the same time.

“Life includes death. They are inseparable. Try to separate them, and you will hurt yourself and others.”

We are all connected. You could label that as something spiritual, but science can prove it too.

Understanding this, you think in terms of ecosystems and community. How does my own death affect my doctors or my family or others? You see relationships as alive compared to this ridiculous notion of the self as this autonomous thing in a vacuum.

Do you have any advice for navigating health challenges or facing death?

If you read the definition of palliative care, you might ask, “Why is that a specialty? Aren’t all doctors concerned with quality of life?” No, they’re not. The healthcare system is wired for acute and curative care. Everything else is treated like a sort of stepchild.

You cannot rely on your doctor anymore to know you very well. Your doctors may change every week. You have to make sure to be known to them. You have to advocate for yourself. That’s a tough pill to swallow when you’re sick. But you shouldn’t move passively through the healthcare system.

All the defaults in the healthcare system are heading towards the intensive care unit where you will be propped up by machines. If you don’t upend those defaults, that is what is waiting for you. So this means doing your advanced care planning and directives—talking with your family and doctor about what’s important to you.

If you’re waiting for doctors to say: “There are no more treatments, go on to hospice,” it won’t happen. There’s almost always something more that can be done. You cannot rely on the medical system to have your best interests at heart: not because it is a malevolent system, but because it’s no longer smart or nimble. It’s overwrought. You need to appreciate that as you plan your care.

It’s helpful to tease out necessary suffering from unnecessary suffering. It’s one thing to accept the pain that comes with being alive. Some suffering is normal and part of the deal. That’s different from the pain that we make up with short-sighted systems that don’t serve people well or include the reality that people experience. We can take a more nuanced view of pain asking: “What do I need to accept, and what can I push back on?”

If necessary suffering befalls us, thanks to nature, that begs acceptance. However, the suffering that we’re creating and heaping on each other and ourselves begs activism to create something better. When you become aware of health care’s unnecessary ills and where it accidentally

hurts people, those become unforgivable, because it’s a man-made invention. We can create something smarter and wiser. And the fact that we don’t feels sadistic, uncaring, unloving and thoughtless.

What should people understand about hospice or palliative medicine?

Hospice and palliative care are poorly understood. Hospice is a form of palliative care that is reserved for the final months of life and tends to people’s quality of life. The focus can feel like it is on death even though the mandate of the two fields is the same: The idea is to live well until you die. We’re not “death happy.” It’s just that death happens, therefore we deal with it.

Hospice emerged in the 1970s. Medicare named hospice a benefit in the 1980s outlining that people need to have six months or less to live and must give up curative-intended care to get it. But we don’t know when we have six months left. There are also many reasons to keep

Dr. Miller published A Beginner’s Guide to the End: Practical Advice for Living Life and Facing Death in 2019, which is an all- encompassing action plan for the end of life treating your illness while welcoming the eventual end. These false barriers end up causing problems. In the 1990s, palliative care stepped into that vacuum and removed the six-month timeline.

“The field asked: Why wait until people are dying to surround them with loving attention?’”

Since 2006, the specialty has been called hospice and palliative medicine. You need to be dying pretty soon to get hospice but not palliative care. You can receive palliative care even while you’re fighting your illness or have years to live. That’s an important distinction.

I’d encourage everyone to get clear on what palliative care is and to ask for it. The earlier, the better. Almost uniformly, people wait way too long to add this kind of care into the mix.

Why is this area of medicine not often at the forefront of discussions about public health crises?

One theory goes back to the mid-19th century when medicine got into bed with the scientific method and innovation. Through our big brains, we labeled illness and death as problems and went to war with them. We were going to beat them. We went to war with death, which is like going to war with life, which is going to war with yourself.

That’s been the dominant thinking for the last 170 years. But that means that when humans, in our arrogance, realize that death still comes no matter what and we can’t fix everything, death becomes a failure. We didn’t try hard enough, or we quit. We throw horrible language around this eventuality that happens to all of us and make it feel like it’s optional. If you’re dying, that’s on you because you didn’t eat enough broccoli or have the right attitude.

Buying into this notion that humans can fix any problem is very seductive. But it’s led to the shaming and bastardizing of normal events like illness, disability and death.

In modern life, we also curate our experience so much. We’ve gotten further away from nature and its cycles. We don’t live on farms or with multiple generations. Aging and death are isolated now. We’re surprised to learn that we die. This was not the case pre-mid-19th century.

Death has become a shameful act that we’re inexperienced with because we rammed it into a closet. A lot of us are trying to shed light on it now, so we don’t have to be ashamed just because we die.

What trends are you seeing in hospice and palliative medicine? What are the major barriers people face when trying to access quality care?

It’s becoming obvious to patients and clinicians that the system is broken. Navigating health care is a pretty miserable experience, whether you’re a patient, family member, doctor or nurse. There’s some hope that by reaching logical conclusions to this curative mindset, we will see a terminus of that thinking. This could force us to reimagine health care, rather than put another piece of duct tape on a system that has ceased to have a coherent design; it’s just a fix on a fix on a fix. I’m hopeful that we’re going to examine the entirety of the system, especially since the aging baby boomers are demanding different care.

An overview of the differences between hospice and palliative care outlined by The National Hospice and Palliative Care Organization representing U.S. hospice and palliative care providers in more detail at bit.ly/HospiceOrPalliativeCare

I’m also hopeful that society won’t wait for medicine anymore. We see this in local efforts like death cafes where people care for each other and don’t wait for the medical system to do it.

We’re seeing a democratization of health, tech and non-doctorly players getting involved, as well as huge amounts of money pouring into integrative and alternative modes of care. Language and popular culture are starting to reflect the realities of humans aging and dying.

Within hospice and palliative care, we’re seeing more acceptance, which is great. But medical system machinery has chewed us up, too. Now, palliative care visits are often only 15 minutes long. We thought we were going to change health care. But in fact, health care is often changing the field. So it’s on hospice and palliative care as a community to fight that reduction.

We will see more social services, more of a focus on social determinants of health and more conversations around quality of life, not just quantity of life. I expect that the public will drive these conversations more than the medical community.

What will it take, in a practical sense, to make the changes you hope for a reality?

First, how we train clinicians is out of date. The last federal review of medical education and training was in 1910 with the Abraham Flexner Report, so that’s the first piece.

The second piece of this puzzle is our health policy, which is also slowly changing. There are over 50 million unpaid caregivers in this country. The policies around family and medical leave need to be revisited, as well as how we pay for care and caregiving. We need to honor that work.

Third, it’s on us, as human beings, to be self-aware and not outsource all our problems to others, not even our doctors. If you look at yourself, you see a piece of nature. Nature does many things. Nature falls apart. Nature dies. It’s on us, as a society, to realize our interdependence. We need to start caring for each other differently.

The fourth piece of the puzzle is infrastructure: communications networks, technology and adaptive equipment that’s beautiful and user-friendly. New hospitals, hospice houses and adult daycare facilities. Virtual care has its limits. We need to find ways to be together in-person again. That’s where a lot of healing happens. I would love to see that every town or

municipality has a hospice house at the center that says: “We care about this issue. We built a beautiful house—someplace you’d want to be.”

What inspired you to start Mettle Health? And how is the model helping reshape people’s experiences when they’re dealing with health challenges?

My partner, Sonya Dolan, and I started Mettle Health in 2020. The pandemic helped us all realize that we are mortal. Using telehealth, we wanted to give people a safe place to fall apart and someone to talk to in the throes of illness, disability and dying.

We started Mettle Health to make palliative care more accessible. To do so, we took on a counseling and coaching model and pulled it out of the medical model. I’m a physician, but if you’re my patient at Mettle Health, I’m not becoming your doctor or prescribing medicines. I’m using my experiences as a doctor to coach you through navigating health care, to help you use the medical system wisely, instead of it using you.

Dr. Miller speaking at Howard Center, a facility focused on providing support and services to address mental health, substance use and developmental needs

We could talk about changing health care on a grand scale, but that’s not going to happen in the timeframe of someone’s illness. As subpar and problematic as the system may be, it’s what we have to work with.

So Mettle Health is a savvy way to help people navigate systems and cope with the realities of illness. We tend to all the existential and spiritual dimensions that don’t fit into a typical doctor visit. We don’t have an electronic medical record, so I’m not typing into a computer when I’m talking to my patient. I’m not limited to 15 minutes with them.

I don’t have to hide behind my white coat and stethoscope. I can share with my patients or offer opinions. We can talk as two human beings. It’s been beautiful to see. This approach allows us to de-pathologize very normal human events.

What lessons from hospice and palliative care apply to other medical specialties?

The rest of medicine can take a more expansive view of healing. It’s the idea of caring beyond the cure: seeing each other through even to endpoints that we wish weren’t the case. That’s not something to be ashamed of; that’s something to love. That means not seeing ourselves as failures for being unable to do impossible things and cure people at any stage of illness.

Sometimes, as a crusader for hospice and palliative care, I find myself pitted against aggressive, intensive or invasive care. But in fact, I’m really not. There’s a time and a place for that, too. For those in palliative care, let’s fix what’s fixable. I’m not against fixing things. But my request is to not be seduced into thinking that it is all there is.

We can all take an approach that includes curing and caring. Don’t think that you have to choose. We can get to a much more nuanced, savvy and nimble mode of care.

What is your ultimate vision for the field? When can we expect to see that vision come to life?

Hospice and palliative care is a correction of a system that lost its way and became out of touch with what actually matters in human life. Health care was hurting too many people. So this little subspecialty came along with the notion that people’s experiences matter. Our feelings matter. Our families matter.

So if you see hospice and palliative care as corrective, maybe someday our work will help health care change positively to become a vital, constructive tool in the world, not one that’s accidentally causing harm or leaving people out. If medicine can heal itself and learn, then hospice and palliative care would go away. I would love to see the moment where these modes of care are integrated as they should be.

Right now, that idea is mostly fantasy. I don’t think I’ll see that in my lifetime. But who knows? We’ve been knocking on this door for decades. Sometimes change is incremental. But sometimes something breaks through the resistance, and the whole thing shifts rapidly. Maybe there has been enough unnecessary heartache that the door will finally just fly open one day.

I have hope. I go to work every day convinced that the changes we’re talking about are possible. I just don’t know when we’ll see them.

This interview has been edited for length and clarity.

If you have any questions or feedback, please contact: curalink@thecurafoundation.com

Newsletter created by health and science reporter and consulting producer for the Cura Foundation, Ali Pattillo, consulting editor, Catherine Tone and associate director at the Cura Foundation, Svetlana Izrailova.