Over the last half century, scientists have made enormous strides in understanding mental illness and developed a robust toolbox of therapies and medications to treat it. But alongside this scientific success, we’ve also seen profound public health failures. Rates of serious mental illness continue to soar and deaths of despair—those related to suicide, alcohol-related liver disease and drug overdose—have more than doubled since the 1990s. Where, exactly, did we go wrong?

To answer this question, we spoke with one of the nation’s leading psychiatrists and neuroscientists, Dr. Thomas Insel. He spent 13 years as director of the National Institute of Mental Health and now works at the forefront of disruptive innovation in mental health care. In issue 19 of CuraLink, Dr. Insel shares the root causes driving mental illness, why the solutions aren’t “rocket science” and our true path to healing.

A conversation with Dr. Thomas Insel

Dr. Thomas Insel, one of the most knowledgeable psychiatrists and neuroscientists in the U.S., is a leader in mental health research, policy and technology. In his 2022 book, Healing: Our Path from Mental Illness to Mental Health, Dr. Insel explores the erosion of the United States’ community-based mental health system and outlines the roadmap to rebuild it.

As director of the National Institute of Mental Health (NIMH), Dr. Insel helped fund cutting-edge science and guide population-based research initiatives.

After 13 years, he moved on to lead the Mental Health Team at Verily (formerly Google Life Sciences) and co-founded Mindstrong Health, a mental health company that applied artificial intelligence to track symptoms and provided app-based care. Dr. Insel later co-founded Humanest Care, a service offering clinical interventions maintained through social support and Vanna Health, a psychosocial rehabilitation start-up.

Through these endeavors, Dr. Insel has been shifting the treatment of mental illness toward a recovery model. By supporting what he calls “the three Ps”: people, place and purpose, he believes we can prevent unnecessary suffering and help people thrive.

Thomas Insel, MD, Author; Co-Founder and Executive Chair of Vanna Health; Co-Founder of Humanest Care and Mindstrong Health and Former Director of the National Institute of Mental Health (2002-2015)

What drew you to psychiatry, and why have you devoted your career to improving people’s mental well-being?

Being of service to people with greatest need was the culture of my family. My dad was an ophthalmologist who worked with underserved populations; my three older brothers all became doctors and I followed suit.

During my late teens, I spent a year traveling around the world wondering where I should work and looking for where there was the most suffering. When I got back and went to medical school, I realized that there was plenty of suffering in the U.S. Mental illness is defined by suffering. Even when we cannot identify a cause, psychic pain defines it. Psychiatry was a field that crystallized a particular opportunity: to make a difference for people who were suffering sometimes more so than with any physical illness.

Dr. Thomas Insel and his three older brothers who followed their father’s footsteps and became doctors

Since you trained, how have you seen the U.S. mental health system and the prevailing approach to treating mental illness evolve?

I trained in the 1970s when psychoanalysis was dominant in American psychiatry. After residency, I went to the NIMH. I was blown away by what was happening there: the early years of the biological revolution in psychiatry that would dominate the next four decades. In a sense, psychiatry in this era went from being brainless to mindless.

This revolution gave us a broad array of new treatments. Fifty years ago, patients and families didn’t have the range of medications, psychotherapies and even neurotechnologies that we have today. While the science has progressed, we lost a system of care and a social safety net that worked pretty well when I was in training.

Through the lenses of families and patients dealing with serious mental illness (SMI), we reverted from a community mental health system to a tragic lack of capacity for helping people with SMI. They are more likely to be in jails or homeless shelters than in the public mental health system—a dystopia that was, frankly, unimaginable when I trained. The tragedy is that we now have many more effective treatments to offer but few people receive high quality care.

Can you share the history behind that erosion?

In 1979, when I joined the NIMH, there was an office in the White House for mental health. But then the federally funded community mental health system, which was set up by President Kennedy in 1963, was abandoned by President Reagan in 1980.

A range of social issues created a perfect storm. The emergence of the war on drugs led to huge numbers of people being incarcerated and veterans flooding into urban areas without any support led to increased homelessness. It was as if the federal government said: “We’re going to wash our hands of this. We don’t want to have anything to do with taking care of people with SMI.”

What are the root causes of the current mental health crisis, and why have we seen such dramatic increases in so-called deaths of despair since the 1990s?

The numbers are stunning. Deaths of despair have more than doubled over the last 20 years and worsened considerably during the pandemic, with young people dying at much higher rates. One root cause is a lack of capacity—the lack of beds, trained providers and a social safety net. But it’s more complicated than that.

I’ve written about the poor quality of care, the lack of accountability and profound equity issues. In writing Healing: Our Path from Mental Illness to Mental Health, one of the major root causes that struck me was the lack of engagement. Why are most people who could and should be in treatment not seeking care?

Some say it’s because of stigma and lack of access or funding. But engagement is more complex; it’s what makes psychiatry more challenging than other branches of medicine. When our patients get sick, whether it’s the hopelessness of depression, the avoidance of anxiety or the denial of psychosis—their core symptoms keep them out of care. The sicker they are, the less likely they are to access care. These types of illnesses are tough challenges for a system that is used to diagnosing, prescribing and medicating. Those alone don’t work here.

Healing: Our Path from Mental Illness to Mental Health, Dr. Insel’s 2022 book, takes an in-depth look at the U.S. mental healthcare system and outlines the ways to reinvent it

Why is tackling mental illness more complicated than treating other diseases?

Brain biology is more complex. We can’t biopsy a brain lesion for psychosis or depression; we don’t understand the basic pathophysiology and we are still unable to map the mind. Mental illness also starts in adolescence or young adulthood when identity is being formed and it becomes a foundational part of many people’s identities. But there is something else that is more difficult to discuss.

If you ask why insurance pays for dialysis but doesn’t cover the basic interventions for psychosocial recovery—coaches, clubhouses, assertive community teams, supportive housing, supported employment—the answer is unpleasant.

Mental health care has not only been carved out; people with mental illness have been cast out. They have become our untouchables. Compared to any racial or ethnic group, they have shorter life spans, lower rates of employment, higher rates of incarceration and greater degrees of homelessness and poverty.

Advocates talk about stigma, but the more appropriate term is discrimination. We don’t send people to jail for diabetes and, usually, we don’t allow patients with dementia to become homeless. It’s not that mental illness is more complicated, it’s that we have refused to care for people who we find foreign and fearful.

There has been major scientific progress in psychology, psychiatry and neuroscience over the past 50 years, but we still have alarmingly high rates of mental illness. Why haven’t these breakthroughs resulted in improvements in mental health?

I started writing Healing to answer that question. On the one hand, there’s huge scientific success. On the other hand, there’s a huge public health failure. Why? Experts say that we have an implementation gap, because it takes 17 years for a discovery to be used in practice.

But I have developed a completely different perspective. The disconnect results from having the wrong model. We’ve been trying to mimic infectious disease medicine, where a simple drug kills a simple bug. With mental health this medical model is necessary but completely insufficient.

We also need a recovery model that requires a lot more than medication. It is not just about reducing acute symptoms but also making sure somebody actually recovers to lead a full and independent life.

What are the keys to alleviating the mental health crisis and true recovery?

To me, recovery is about the three Ps: people, place and purpose. It requires social support, a nurturing environment and a purpose to get up every day.

The problem is medical. These are brain disorders that deserve the same research, rigor and reimbursement as any other medical condition. We need acute symptom relief, but it’s just not enough. The solutions are so much more than a pill or an office visit. They are social, environmental and political. They need to include the three Ps.

Peer support is essential to help people recover, and we know how to provide it, along with a healthy environment and a mission. When I began my career 50 years ago, we thought about it this way. We did not have all the medications or bespoke therapies. But we made sure that people had housing, were reconnected with family and had social support. We tried to provide job training or reconnect patients to some kind of work. We had programs like Fountain House, which is 75 years old, where people gather and support each other every day, kind of like AA. Now there are over 300 of these clubhouses in over 30 countries.

This is not a new or complicated approach. But it doesn’t happen. Less than 1% of people with SMI have a clubhouse nearby. Of the various effective rehabilitative services, under 5% of people with SMI get work and housing support. Why? It comes down to what we pay for. We pay for pills, hospitalizations and ER visits. But public and private insurance does not support most of the rehabilitative care essential for recovery.

As with acute care, we need to expand mental health care to include recovery services and the three Ps. In renal failure, people don’t go to community-based nonprofits for dialysis. If you get hit by a car and break your leg, you don’t go to a small community agency staffed by volunteers to get physical therapy.

Dr. Thomas Insel at the STAT Breakthrough Summit in San Francisco (May 4, 2023). Photo by Sarah Gonzalez for STAT

In a nation that spends $4.3 trillion on pills, office visits and hospitalizations, it seems outrageous that recovery services are left to community-based nonprofits surviving on bake sales and auctions. In the rest of medicine, we understand that rehabilitative care is part of recovery and essential for health care. Not here; not for mental health.

Why don’t policymakers, insurers and financial stakeholders reimburse these services?

From a policy angle, it seems too vast and difficult. The irony is that we do it in a more intensive and ineffective way, spending more money than we need to. As I wrote in a May editorial in The Washington Post, a year in a clubhouse costs less than two weeks in an inpatient unit. It’s really not that expensive. But there’s a tradition in health care of carving out behavioral health (both substance use and mental illness). Nobody wants to deal with it.

Patients with SMI are about 11 times more likely to end up in the criminal justice system than in the healthcare system. Tonight there will be about 380,000 people with serious mental illness in jail or prison and about 34,000 in public hospital beds. Something is not right about that.

We’ve recently seen a boom in digital mental health solutions, from meditation apps to counseling chatbots—all of which will be accelerated by artificial intelligence. Have these innovations helped address the mental health crisis?

I think of the digital mental health revolution as a five act play, and we just finished act one. By act five, mental health care will be fully transformed, more than any other area of medicine, because digital innovation tools are really effective for language and conversation. That is what mental health is all about: communication, relationships, listening and observation.

At this point we have seen huge investment, a new industry that is democratizing access and the aggregation of private practices by private equity. We have not seen an increase in quality, a demonstrable improvement in outcomes and a commitment to people with SMI.

“Disruptive innovation is essential here. But let’s not neglect those with the greatest need.”

In the very near term, we need a regulatory framework, not just to protect consumers, but to help developers understand what success looks like and what to build for.

Are the current treatment options adequate? And what developments on the treatment side would you like to see to make a meaningful difference?

We have four modes here: medication, psychotherapy, neuro-technologies like transcranial magnetic stimulation and rehabilitative care. All four are very effective, but they need some improvement.

- Better payment: For these treatments to be delivered, they need to be paid for. There is a continuing lack of parity: Mental healthcare reimbursement is significantly less than physical healthcare reimbursement even though we know that the presence of an untreated, comorbid mental illness makes physical health care more expensive and less effective.

- Better targeting: We need to better understand who should get which treatment, when and in what dose. Medication treatment is still too much an exercise in trial and error until we find the right drug or the right combination. More precise diagnostic categories can help.

- Better quality: We have evidence-based psychological therapies, but most of our therapists were never trained in any evidence-based treatments. We have treatments that really work, but very few people are using them. Again, hard to imagine this situation for diabetes or hypertension, but this field has not prioritized quality.

- Better coordination: For mental health care, you go to your primary care doctor to get medication; you go to a social worker for psychotherapy. The field is so fragmented, that people tend to get one of the four treatments, not a combination of them, which is probably optimal.

When much of the biological and biochemical nature of mental illness isn’t well understood, what’s the role of precision medicine?

When I was at NIMH, I thought that the key to improving diagnosis was going to be genomics and imaging—two powerful approaches that have transformed diagnosis in many other areas of medicine. That hasn’t happened here. Neither of those fields has delivered biomarkers that are being used in practice. Maybe these approaches will deliver in the future. Already electroencephalography and machine learning are beginning to create some predictors of treatment response.

“The royal road to better therapeutics is better diagnostics.”

Biomarkers will help, but we may not need blood or imaging tests. We keep assuming that the biomarkers that have worked for cancer and heart disease will work in psychiatry. In our zeal to be like the rest of medicine, we have neglected what we should do best—precisely defining behavior measured ecologically over time. We just need to do a better job of measuring sleep, activity and socialization. And we can learn so much from objective measures of voice, speech and facial expressions. We now have outstanding tools to be able to get highly precise data on behavioral measures. These measures may yield the kinds of biomarkers we need for precision psychiatry.

What lessons did you learn during your time leading NIMH, and how do those lessons inform your current endeavors at Vanna Health and Humanest Care?

My time at the NIMH was one of the best chapters of my life. I was fortunate to be there during The Brain Research Through Advancing Innovative Neurotechnologies® Initiative, the genomics revolution, several historic clinical trials and the studies of early psychosis. But the practical question we never asked was: “Who is going to pay for this?”

In the U.S., health care is simply a business. The care you get is the care that gets paid for. One of the biggest problems at the NIMH, and the NIH generally, is that we support an academic community that is increasingly focused on writing papers not solving public health problems. Particularly in the mental health space, we have done such extraordinary science and yet the outcomes are more dire every year. NIMH is a research funding agency not a service delivery agency so we can’t blame NIMH for the outcomes. That said, I worry that our scientists are not creating the solutions that healthcare systems will adopt. What we called our implementation gap was simply our failure to work out the unit economics of a new diagnostic or treatment. No payment, no adoption.

“Ultimately, the dysfunctional system we have today is exactly the system we pay for.”

So we have to change the incentives and move toward an outcome-based payment system that says: “This is what we care about—reducing incarceration and reducing suicide and recovery—and we reimburse accordingly.” Until we do that, we aren’t going to move the needle.

When I joined Vanna Health, one of the founders told me that he really liked the idea of the 3 Ps, but he thought I had left off a P. I assumed he meant prevention, but he said, “No, payment. If you don’t have payment, the other 3 Ps don’t happen.”

Of course, I was still thinking like an NIMH scientist. So at Vanna, we innovate on payment by developing risk- and value- based strategies that support recovery services.

How do we accelerate insights moving from the academic setting to the real-world settings?

I was always asked: “How do you go from research to practice?” But we need to go from practice to research. We need to ensure that people who are on the front lines are collecting data in a way that is harmonized, consistent and of high fidelity.

That’s how we build great products in the tech industry. At Google, I learned to start with the user experience. Our healthcare system doesn’t work that way. If you want to build stuff useful in practice, you start with people in practice.

You build with them, and you build for them.

Have any other countries had success in taking a more value-based care model and a more holistic approach to mental health?

The United Kingdom has greatly improved the quality of psychotherapy, and it shows in their outcomes. In northern Italy and Scandinavia, people have taken on a recovery care model and seen better outcomes, too. Experiments are happening in Peru and Costa Rica. So there’s real interest in many places and a legacy of better practices. But I don’t think we found a Camelot for mental health care yet.

Getting to a value-based model means ending the carve out for mental health care, measuring outcomes and defining value. If this has happened at a population health level, I have not seen it.

Anthony Fauci, MD, Former Director of the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases; Francis Collins, MD, PhD, Former Director of the National Institutes of Health and Thomas Insel, MD, Former Director of the National Institute of Mental Health, circa 2015

The pandemic taught us that we could move faster than ever before to address public health issues. Are you seeing evidence that leaders are moving faster and with more urgency on mental health issues like they did with COVID-19?

Yes, leadership matters. There are some promising signs. Surgeon General Dr. Vivek Murthy’s focus on youth mental health is historic. California Governor Gavin Newsom made unprecedented commitments, particularly for homeless people with SMI. He’s also trying to create a new behavioral health support system for children by making schools the “center of gravity” for mental health. The leaders of major advocacy and professional groups have come together in the CEO Alliance to create a unified vision to address mental health.

All of this is promising, but we need a campaign like Operation Warp Speed. It’s tough, because families struggling with a young person with schizophrenia don’t have the bandwidth to march, protest and write letters to make the rest of us realize their situation. I talk about the 40-40-33 rule: 40% of people with mental illness receive treatment, 40% of those receive minimally adequate treatment and 33% of those get full benefit. We need a campaign that commits to 80-80-50 by 2030. That’s what it will take to bend the curve for morbidity and mortality.

What changes do you hope to see over the next decade, and what is realistic to expect based on the current conditions?

The critical, urgent issues—reducing incarceration of people with SMI, treating homeless people who are psychotic, ending emergency room boarding and reducing suicide by firearms—can be solved rapidly with common-sense policies. We need leadership, a social movement and clarity that none of this is inevitable.

I am hopeful. This is a crisis but, unlike COVID-19, it has not fallen into the culture wars. Mental health is bipartisan; it is personal. I am hopeful because we know what needs to be done.

Sixty years ago, when President Kennedy signed the Community Mental Health Act of 1963 he said people with serious mental illness “need no longer be alien to our affections or beyond the help of our communities.” The time is long overdue to deliver on his vision.

This interview has been edited for length and clarity.

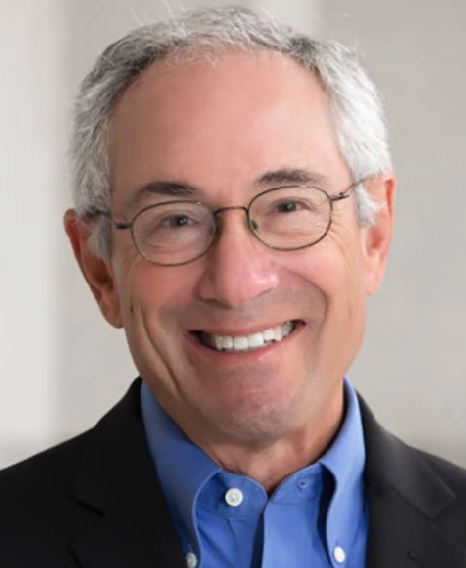

On September 2, our community lost Dr. Max Gomez. He passed away at age 72 from an extended illness. Dr. Max was an extraordinary individual, a wonderful friend and a one-of-a-kind medical journalist who helped make medical and scientific information more accessible. It is with heavy hearts that we at Cura say goodbye to our trustee and friend Dr. Max.

The Cura Foundation lost our beloved trustee, Dr. Max Gomez, on September 2. Dr. Gomez passed away after a long illness at age 72. He was the chief medical correspondent at CBS2 in New York. Lovingly known as Dr. Max, he was deeply loved and respected by colleagues in the newsroom, medical professionals and scientists he worked with and the patients who shared their stories with him.

Dr. Max Gomez with His Holiness Pope Francis in 2018

In 2021, Dr. Gomez was recognized by the Vatican’s Pontifical Council for Culture with the Pontifical Hero Award for Inspiration for educating the public, leading by example, and providing hope to millions of viewers in crisis. Throughout his career, Dr. Max earned nine Emmy® Awards, three New York State Broadcasters Association awards, UPI’s Best Documentary award for a report on AIDS and an Excellence in a Time of Crisis Award from the New York City Health Department after 9/11, an honor he cherished.

In addition to being a trustee of the Cura Foundation, Dr. Gomez also served on the national board of directors for the American Heart Association, the Princeton Alumni Weekly and Partnership for After School Education and chaired the national communications committees for the American Heart Association and the American Association for the Advancement of Science.

Dr. Max was born in Cuba and later moved with his family to Miami. He graduated cum laude from Princeton University, earned a Ph.D. in neuroscience from the Wake Forest University School of Medicine and was an NIH postdoctoral fellow at Rockefeller University.

Dr. Gomez is survived by his children Max Gomez IV and Katie Gomez.

If you have any questions or feedback, please contact: curalink@thecurafoundation.com

Newsletter created by health and science reporter and consulting producer for the Cura Foundation, Ali Pattillo, consulting editor, Catherine Tone and associate director at the Cura Foundation, Svetlana Izrailova.