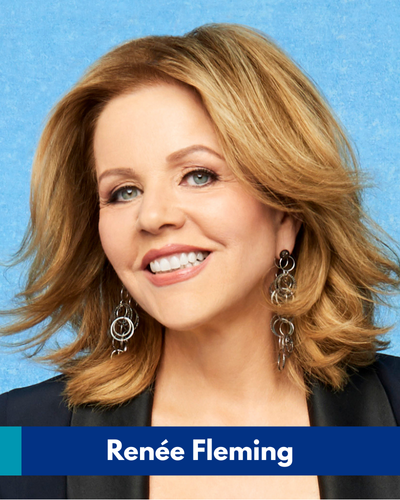

We are incredibly fortunate to share a fascinating conversation with the living legend, Renée Fleming. Throughout her prolific career, Ms. Fleming has not only shared her extraordinary musical gifts with the world but worked tirelessly to expand arts education to everyone and advance the scientific study of the arts to better understand its therapeutic effects, too.

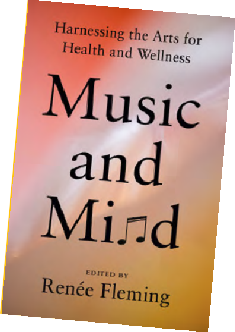

In her new anthology of essays from leading scientists, artists, creative arts therapists, educators and healthcare providers, “Music and Mind: Harnessing the Arts for Health and Wellness,” Ms. Fleming highlights how the creative arts shape our lives. It turns out that engaging with art—whether it’s listening to music, drawing or dancing—activates the brain and body in ways we are just beginning to understand. The arts may be a vital antidote to help us deal with our chaotic world.

A conversation with Renée Fleming

Creating and experiencing art is universal for humans. Since before humans could speak, they’ve sung, painted and played instruments, making the music and art that colors our lives. Emerging data in arts and science research shows that the arts have powerful effects on the mind and body.

World-renowned soprano and arts and health advocate Renée Fleming has devoted her life to music. One of the most highly acclaimed singers of our time, she has performed at the world’s greatest opera houses and concert halls as well as on momentous occasions, including the Nobel Peace Prize ceremony and the Super Bowl. Ms. Fleming has received the U.S. National Medal of Arts, the 2023 Kennedy Center Honor and five Grammy® awards.

A leading advocate for research at the intersection of arts and health, Ms. Fleming launched the first ongoing collaboration between the John F. Kennedy Center for the Performing Arts and the U.S. National Institutes of Health. She is also the World Health Organization’s Goodwill Ambassador for Arts and Health. Her new anthology, “Music and Mind: Harnessing the Arts for Health and Wellness,” showcases how the creative arts are an underutilized, non- invasive and affordable tool in the fight for better mental and physical health.

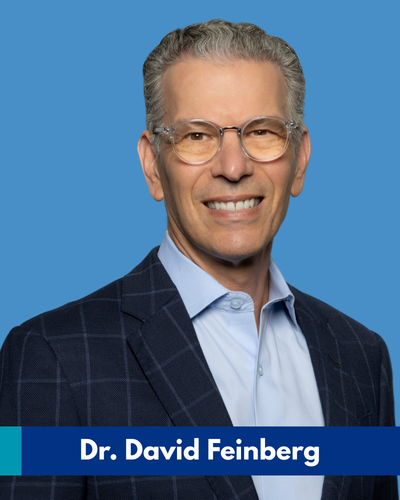

Renée Fleming, Soprano; Arts and Health Advocate; Artistic Advisor, John F. Kennedy Center for the Performing Arts and Editor, “Music and Mind: Harnessing the Arts for Health and Wellness”

What is your earliest memory of connecting with music?

My parents were both music teachers. At a very young age, I was under the piano listening to my mother teaching voice and piano lessons. Music was my first language and wired my brain in a way. My parents say I sang before I spoke, which makes perfect sense, considering I spoke quite late. This is in touch with our evolutionary roots: Researcher Dr. Aniruddh Patel at Tufts University noted that human ancestors likely sang to communicate before developing spoken language.

My first memory of being obsessed with music was listening to “Peter and the Wolf” by Sergei Prokofiev, a story set to complex orchestral music. I loved it and played it over and over. That’s probably why I love contemporary classical music.

When did you realize that you possessed a gift of innate musicality?

I didn’t think I had a gift. I assumed everyone was musical because of my own family. On long cross-country road trips, we would sing the road signs in harmony. I was surprised to discover that other families didn’t do this.

The gift for me was being able to write music throughout middle and high school. I was very shy, a bookworm and quite reserved, and composing gave me an early creative outlet to express myself. Because I wasn’t innately gregarious, I developed a love-hate relationship with performing. Eventually, once I became more comfortable expressing myself, I stopped composing and focused on my education.

How did your musical education evolve?

During my childhood, I did a bit of everything—studying piano, viola and dance; musicals in high school; classical concerts and other genres. I was fortunate to have a very robust arts education in the public schools where I grew up.

In college, I majored in music education, studying classical music. It involved a complex training regimen of music theory, counterpoint, solfège, singing in up to 10 foreign languages and mastering distinct performance styles across centuries of music. Now, many programs offer jazz or music theater, too. I also sang jazz on Sunday nights for two and a half years, which was an incredible education in itself.

Dr. Charles Limb at the University of California San Francisco performed an fMRI study with highly skilled jazz musicians and found that the lateral prefrontal cortex of the brain disengages during improvisation. This area controls conscious self- monitoring and inhibition. Improvising overrides the brain’s self-judgment and engages its self-expression. You must let go

or you can’t reach the flow state required to improvise. For me, improvising was a fantastic education; it was freeing and how I discovered an upper part of my voice that I probably wouldn’t have otherwise because I wasn’t judging myself.

Although I was invited to go on the road with the famous tenor saxophonist Illinois Jacquet during my junior year, I chose graduate school because I felt more comfortable in an academic environment.

You’ve experienced terrible bouts of somatic pain tied to stage fright and performing. Can you describe those episodes and what have they taught you about the mind-body connection? How did you shift your mindset and overcome the pain?

Our minds try to find ways of protecting us, but the defense mechanisms aren’t always helpful. It seems to me that my somatic pain was protective in a sense. Research from the University of Gothenburg in Sweden indicates that somatic symptoms, such as headaches, palpitations and musculoskeletal and joint pain, are strong predictors of acute anxiety. Essentially, the pain occurred to keep me from the anxiety- inducing experience of performance.

I used to see the audience as very judgmental. To get past episodes of stage fright, I had to completely change my thinking around performing. I had to see myself as sharing something beautiful with the audience, becoming a conduit for what composers and poets had created, instead of interpreting the audience’s attention as negative. This realization made all the difference.

“Any positive aesthetic experience is very powerful and healing for us humans.”

Another factor behind my somatic pain was a success conflict. As my star rose, I felt like I was in the wrong place. Many people talk about imposter syndrome—feeling like they’re frauds. We see this with actors, performers and politicians who self-sabotage their careers with detrimental behaviors. Barbra Streisand stepped away from live performance for over 20 years because of anxiety. Performance pressure almost derailed my career.

Renée Fleming highlights how creative arts shape our lives in her new anthology of essays from leading scientists, artists, creative arts therapists, educators and healthcare providers, “Music and Mind: Harnessing the Arts for Health and Wellness”

How do you feel when you are performing or listening to music?

I’m in a flow state when I perform, completely in the zone. Dr. Limb notes that in a flow state, creativity allows your brain to be the best functional version of itself, whether performing, cooking or even in surgery. When I’m comfortable on stage, which is almost always, it’s fantastic. When I perform certain pieces, I feel my heart rate and breathing slow down. Dr. Deepak Chopra once told me: “You’re lucky that you’re a singer. You’re stimulating the vagus nerve every time you open your mouth.”

Singing offers powerful benefits for many health conditions. Dr. Jacquelyn Kulinski at the Medical College of Wisconsin has shown that singing at least twice a week for half an hour increases vascular function in patients with cardiac failure. In research from University College London and the World Health Organization, singing in a choir helped alleviate severe postpartum depression symptoms in women. Additional studies showed reduced loneliness and isolation for those singing in choirs, especially for older adults or for patients with stroke or Parkinson’s disease. Aside from the pleasure of making music, your brainwaves align with other singers and the audience, creating positive social interactions. For me, singing is a privilege, and I love connecting with the audience.

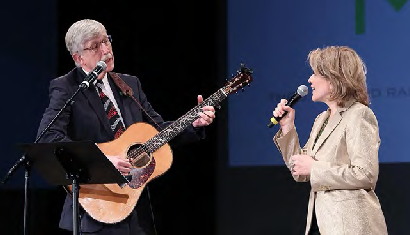

Ms. Fleming sings with Dr. Francis Collins

When did you meet Dr. Francis Collins, who became a longtime collaborator and wrote the foreword for Music and Mind?

I met Dr. Francis Collins at a fantastic dinner party outside Washington, D.C. Three Supreme Court justices were present: Antonin Scalia and Ruth Bader Ginsburg, who were both opera fans, and Anthony Kennedy. It was the day after marriage equality was decided, so it was a little tense at first.

But Francis brought his guitar and started singing with the band there. We all joined in and ended with “The Times They Are A-Changing.” That night, I had the chance to ask Francis about the burgeoning neuroscience of music and the brain. I had just been appointed Artistic Advisor at the Kennedy Center, and ultimately, we launched a lasting first-of-its-kind partnership between the Kennedy Center, the National Institutes of Health (NIH) and the National Endowment for the Arts. It’s been a fruitful collaboration ever since.

What have you learned about how the arts affect the mind and body?

The way in for me was evolution. Dr. Patel’s chapter on this in my anthology is a fabulous explanation of why the arts are so powerful to humans. The arts are ancient; they pre-date speech. From cave paintings and artifacts like a 40,000-year-old bone flute, we know that, for the earliest humans, artistic expression contributed to social cohesion, which was crucial for survival. Historically, humans have always used music to celebrate or mourn at major life events like weddings, funerals, wars and rituals. This is how we became hardwired for the arts.

“Humans are tribal. We need positive arts activities that facilitate togetherness and connectedness.”

Dr. Daniel Levitin’s and Dr. Nina Kraus’ chapters on brain neuroanatomy and our perception of sound are also fascinating. Dr. Levitin explains that because music exists so pervasively in the brain, music memory is one of the last capacities to be lost to dementia, especially songs from the teen years when the brain is incredibly plastic. Late in life, those songs activate powerful connections to memory. Dr. Kraus introduces us to the brain’s ability to decipher sound, with a nod to human survival throughout history. Who hasn’t walked down a dark street at night with a heightened awareness of sound? Dr. Kraus also discusses the complexity and intangibility of sound and hearing, the last of our senses to be researched, and how we can use sound to better understand childhood development and even concussions.

What insights have surprised you in this work?

The research on music and pain is astonishing. One of my friends had a brain bleed recently. She was in excruciating pain, couldn’t look at screens and had to be in the dark. Only one thing alleviated her pain: listening to Jimi Hendrix as loud as possible. If the volume decreased or the music stopped, the pain came flooding back.

After hearing this, I asked my connections at the NIH about it. They sent me fascinating studies showing that listening to music can relieve even the most severe pain. Scientists don’t agree on whether music distracts from pain or prompts certain brain parts to actively reduce the pain sensation or perhaps both. But it does often appear to work. Researcher Dr. Joke Bradt at Drexel University demonstrated the effectiveness of music therapy in alleviating chronic pain.

Dr. Bradt also found that vocal music therapy and active music-making can increase self-management, motivation and empowerment and reduce isolation.

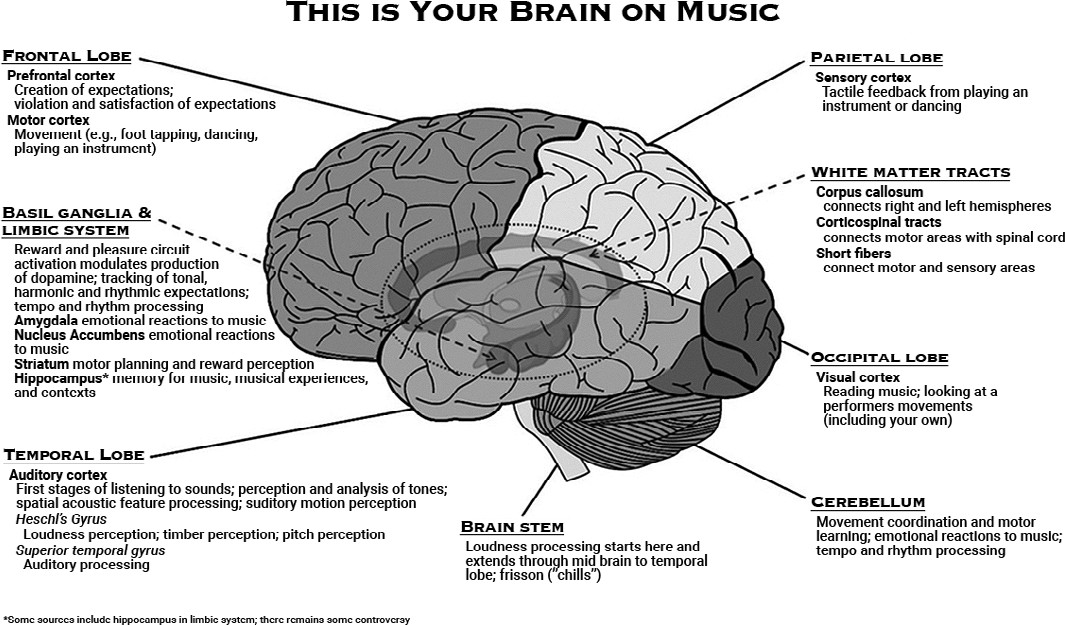

Similar to vision, music activates nearly every region of the brain. Specific circuits handle pitch, duration, loudness and timbre and higher brain centers bring this information together. Illustration © 2024 Daniel J. Levitin

In the past, some people might have seen this sort of arts and science research as “soft science.” How is that perception changing with new technology and emerging data?

You’re right. When I started this work, I was still hearing that term. I don’t anymore. It is partially attributable to the NIH; they’ve spent nearly $40 million so far on arts and health research, particularly music. They’re adding dance because of potential applications in Parkinson’s, multiple sclerosis and traumatic brain injury. The amount of rigorous research is increasing, but it’s all still relatively new.

Clinical successes are also tipping the scales, and hospitals are adding creative arts therapy studios and practitioners to their staff. The COVID-19 pandemic was certainly an “aha” moment for everyone. Music therapy shows tremendous promise for breathing difficulties, improving pulmonary health, reducing dyspnea (shortness of breath) and relieving anxiety in patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Music therapy also offers patients a sometimes more appealing activity than other forms of pulmonary rehabilitation.

Working in this field, I have been welcomed by arts and science communities and general audiences. I don’t present myself as an expert, and I’m not. But I am thrilled to share the latest discoveries with the public. I’ve given over 60 presentations around the world, often with local researchers, healthcare practitioners or therapists. People get very excited and ask: “What can I do?” The book is an introduction to invite more people into this work.

How do creative arts influence child development and the developing brain?

A strong body of research shows that learning an instrument is incredibly beneficial for children. There are lasting changes in the brain after just two years of study. It fosters self-discipline and focus because to master an instrument, practice is necessary. Cooperative and interactive skills are developed, especially singing or playing in a choir or ensemble. Auditory learning is improved, and the benefits extend to other areas like math and reading comprehension.

Arts programs also provide massive benefits in K-12 education. In the wake of the pandemic, widespread truancy has become a major challenge. However, many children will stay in school if you provide activities that they love, help them create a sense of identity and allow them to be self-expressive. Sadly, we’re seeing some of these programs cut.

Another fascinating application involves teens with cancer who just aren’t interested in talk therapy to discuss how they feel. But they express themselves if you ask them to write lyrics to a hip-hop song. Each year, 72,000 teens and young adults are diagnosed with cancer, two-thirds of whom will have long-term effects from their treatment. Dr. Sheri Robb spearheaded a study with adolescents and young adults undergoing stem cell transplants for cancer. She introduced a behavioral

intervention of songwriting and film editing and found that patients developed more positive forms of coping and a strong social support system that boosted resilience. Similar music therapy and visual arts therapy treatments have helped veterans with post-traumatic stress disorder.

What therapies are you most excited about?

One of my favorite interventions is melodic intonation therapy used to help regain speech after traumatic brain injuries. “Music Got Me Here” is a moving documentary about music therapist Tom Sweitzer and his work with a teenage boy recovering from a horrendous snowboarding accident. This therapy gave the patient, Forrest, his speech back.

Melodic intonation therapy leverages neuroplasticity. In this case, Broca’s area of the brain’s frontal lobe is linked to speech. But this function can transfer into another part of the brain used for singing because lyrics are a form of speech. Some people can start to communicate again in just one session with a music therapist. In Forrest’s case, his recovery was long but extraordinary. Thank God he was so young. This therapy has also been effective with veterans, as well as patients with strokes and other forms of aphasia.

Should health providers be prescribing creative arts therapy and insurers covering it?

Absolutely. Right now, it varies state by state. As of June 2024, only 12 states have licensure for music therapists. Some states help cover payment, but, usually, it’s dependent on philanthropy.

The big lift is creating more universal standards and expanding coverage for arts therapies in the way that modalities such as acupuncture are covered today. The integrative medicine team at the NIH is focused on this, among other topics. We will get there.

“There’s no question that creative arts therapy belongs in health care.

What advantages does creative arts therapy have?

Creative arts therapy is low-cost, non-invasive and non-pharmaceutical. Music, especially, impacts every single mapped part of the brain. There’s no other activity that’s so widespread neurologically.

There’s a broader emerging field of neuro-aesthetics—how the arts change the body, brain and behavior. Research shows that doing any art activity for 45 minutes will reduce anxiety by 25%. These activities help people to slow down.

The economic argument will ultimately be more compelling than the research argument because healthcare providers and insurers really care about the bottom line. One study done by AARP and KPMG showed that having the arts in elder care, particularly for Alzheimer’s patients, gives a three-to-one return on investment.

No new children’s hospital should be built without a creative art studio. The benefits for children and their families are powerful. There’s a video from C.S. Mott Children’s Hospital in Ann Arbor, Michigan, of an 11-year-old girl in distress before having induced seizure testing. Her music therapist has her sing a song, which calms her down immediately.

Renée Fleming is a world-renowned soprano and a recipient of the U.S. National Medal of Arts, the 2023 Kennedy Center Honor and five Grammy® awards

“Arts therapy shouldn’t be an extra add-on if people have the resources or time; it should be a frontline treatment.”

How can everyday people harness the arts in their daily lives?

I’m doing it now. On January 1, I pledged to spend time away from my newsfeed and instead give myself some kind of creative outlet that I love every day. I can’t tell you how much happier I am. I go to the theater and concerts, read novels, listen to music and walk outside. I’m infinitely happier. It really works.

What about people who say they don’t have the time?

I thought that, too, but I realized I had all this wasted time. I am on a plane nearly every other day. All that time spent getting to the airport, checking in, walking to the gate and waiting for the plane is empty. Now, I listen to either music or books. I use this time for my own sense of well-being. We are all worth it.

With anything you do that’s slightly mundane, like grocery shopping, you can find ways of enhancing your brain by either listening to music, books or podcasts. Fiction is especially good because you use working memory to listen to it.

You are involved with many arts and science initiatives through your Foundation and partnerships. What do you hope to achieve, and what progress have you seen?

When I first started doing presentations around the country, I immediately saw that there was redundancy. I learned from experts that many studies were not very well designed or did not have large enough populations. So I helped fund a project with the NIH to develop a toolkit to improve the quality of research. To be awarded a grant, your proposal needs to have certain elements and adhere to rigorous standards. The toolkit was a practical way to help researchers do this work.

Renée Fleming speaking at the NIH, 2019

The Sound Health Network, an initiative of the National Endowment of the Arts, has grown tremendously. For anybody interested in the arts or research, that’s the place to go. And there’s a new global resource center on creative arts in development as part of the NeuroArts Blueprint, a collaboration between Johns Hopkins and the Aspen Institute. That will move the needle significantly. The project includes a tremendous vision document for how creative arts can become a field in health. Similarly, climate change was not a field a few decades ago. Now, it’s a major one.

These are the kinds of initiatives we need. Across the country, arts education teachers are scarce. Many arts programs have been cut from public schools. So that pipeline needs support. If you add creative arts therapists to schools, you could also promote prosocial behavior. You boost the morale of both teachers and students. It’s vital.

What are the biggest hurdles standing in our way to making arts more accessible?

First, we need to continue to strengthen the research base. I recently funded a series of investigator awards with the NeuroArts Blueprint and the Aspen Institute for seven young scientists who are either artists or working with artists. The caliber of these award recipients is extremely high, and this is only the first year. I’d love to grow the number of sponsors and awards to further encourage scientists to incorporate the arts.

Dissemination is a big issue. You might have the best research in the world. But if people don’t know about it or doctors don’t know how to use it, it will have no effect. That takes a long time.

Lastly, advocacy—making people aware of the benefits and advantages when more conventional invasive or pharmaceutical therapies are the status quo. Imagine that you can regain speech after a stroke in one session of melodic intonation therapy. How many people in the country know about that?

What is your ultimate vision for the arts being embedded in health care?

I was at Yale recently with Dr. Laurie Santos, who has this incredibly popular podcast called The Happiness Lab. The Schwarzman Center student building has spaces to rest, relax and reduce anxiety, listen to music or create art and gather socially. Other universities are picking up this cue quickly in response to the need for mental and emotional well-being for students.

Since the pandemic, many people have been apprehensive about attending live performances. But now that we have science behind the benefits of shared experiences where your brainwaves align, we know live performances are critically important. Scientists at MIT, for instance, just published an amazing discovery of universal brain wave patterns across mammalian species. The researchers said: “We can’t believe we missed this, this was in plain sight.” This will spawn a huge amount of research.

The future will be about technology and music. There’s an incredible company called Neuroscape using virtual reality (VR), which has tremendous potential to help people. Imagine if you’re in an elder care facility with no mobility. You can put on a VR headset and escape, feel, see and experience many things, including awe and transcendence, both areas of recent research.

What would you want readers to understand?

For health providers, I’d encourage learning about the power of creative arts therapies to help their patients. Programs and resources are available, but few know about them.

One initiative I’d like to see launched is ArtCare to connect people to existing resources by zip code. Almost all performing arts centers have great programs for children with special needs, as well as patients and caregivers. Spreading awareness about them is the challenge.

I would encourage people interested in health care to think about how they can serve and share their gifts. That’s not something that my generation has been very good at. We’ve been the “me generation.” I hope this begins to change because there is so much need worldwide.

This interview has been edited for length and clarity.

If you have any questions or feedback, please contact: curalink@thecurafoundation.com

Newsletter created by health and science reporter and consulting producer for the Cura Foundation, Ali Pattillo, consulting editor, Catherine Tone and associate director at the Cura Foundation, Svetlana Izrailova.