Our next expert is Dr. Jeremy Cauwels, who is reimagining rural medicine in the United States as chief physician at Sanford Health. With a pressing labor shortage and escalating health disparities, Dr. Cauwels discusses how to overcome key barriers related to rural health care with modern technology.

Health systems, rural or not, can benefit from his insights to better reach patients no matter where they live.

A conversation with Dr. Jeremy Cauwels

The American healthcare system is facing a crisis of alarming proportions: Rural Americans are at a greater risk of death from five leading causes including heart disease, cancer, unintentional injury, chronic lower respiratory disease and stroke than their urban counterparts. Yet, despite these health disparities, resources remain scarce. While approximately 15 percent of Americans live in rural areas, only 11 percent of physicians practice in these communities.

Sanford Health, the largest rural health system in the United States, is dedicated to bridging this health care divide and providing access to world-class health care in America’s heartland. Headquartered in Sioux Falls, South Dakota, the organization serves more than one million patients and 220,000 health plan members across 250,000 square miles.

Sanford Health is harnessing 21st-century telemedicine and training the latest generation of physicians and nurses to connect on the patient’s—not the provider’s—terms.

This month, Sanford Health’s Chief Physician Dr. Jeremy Cauwels shares their innovative strategy, which includes a virtual care center, Main Street clinics and new approaches to “webside manner,” that paves the way for other health systems to improve access for all.

Jeremy Cauwels, MD Chief Physician at Sanford Health

How did your upbringing in Iowa shape your approach to rural medicine? Did any early interactions with the local health system influence how you practice medicine today?

I grew up in a small town of about 2,000 people in Northwest Iowa and graduated high school with 38 of my closest friends. As a child, I was familiar with the challenges of living with a chronic condition in a rural area and traveling long distances to receive the necessary care. I was diagnosed with congenital heart disease and the University of Iowa was the closest place for me to access care, which was a five-hour drive from our house. So, my parents would have to take a couple of days off work for each visit. This experience informs my work at Sanford Health and exemplifies why we need to rethink our approach to rural medicine and do better.

As Dr. Eric Topol has expertly written, it should be about: “The patient will see me now,” not “I will set something up, and the patient has to conform to my rules.”

Sanford Health’s virtual approach to obstetrics care has reduced in-person visits and increased convenience for patients

Do any key lessons stand out from your experience as a physician practicing in rural America?

Based on my experiences, what is clear is that patients often travel tremendous distances for follow-up visits that could be conducted virtually.

One classic example at Sanford is in obstetrics. Pregnant patients of normal risk are typically seen biweekly, or even every few weeks, as they get closer to delivering their babies. Those are typically 10-minute appointments, and if you see that the patient’s blood pressure is normal, the fetal heart tones look good and the mom is feeling well, you probably do not need to see them in- person as often.

That is something that Sanford adopted prior to the pandemic. Dr. Allison Suttle (now chief quality officer at WVU Health System) developed an evidence-based OB video visit program for low-risk pregnancies. We can give a mom a kit with a blood pressure cuff and a Doppler ultrasound, send her home and see her in-person 50 percent as often. We will have just as many appointments, but we will do them virtually.

For patients living in rural communities, what is it like to experience a health emergency far from the nearest hospital?

During the COVID-19 pandemic, my father had a quintuple vessel coronary bypass. He noticed his symptoms while working on his roof, and he had to climb down the ladder knowing that he was 70 miles from the nearest catheterization lab. Luckily, my dad did very well. But that is a regular occurrence in the world that I live in.

People are often 50, 60, 100 or even 200 miles from the nearest “perfect facility” for treating them for a stroke, heart attack or other acute condition. What we have done at Sanford Health is expand the digital footprint of our stroke specialists in Sioux Falls or Fargo by connecting them to smaller facilities.

Discussing the patient’s symptoms and available treatment options in real-time via digital link with clinicians before transport could be potentially lifesaving. That way, the treatment begins as though you are in one of our stroke centers before you are within 100 miles of one.

That is the type of bidirectional communication we need to have every day to make sure we bring the care to where the patient needs us, not where we need the patient.

What are the major driving factors behind the rural-urban health care divide (resources, personnel, affordability, etc.)? What are the most persistent challenges in rural health care delivery?

One key issue is provider shortages. Physicians, nurses and respiratory therapists are not plentiful in rural areas and certainly not in small hospitals.

Another thing is connectivity. Does the patient have the access where they live to obtain a reliable connection to their providers? In the town I grew up in, for example, we were lucky enough to have a community hospital. But the six small towns around us did not have that community hospital access. They had to drive at least 30 miles to get care.

We are pushing very hard to have one-on-one interactions with folks. We are also pinpointing the health care deserts across the map of our facilities. How do we create services on Main Street of a small town that may not house a doctor but may house a digital connection to the specialist that people need to see?

We have pilot clinics where we can start providing care to folks before they ever physically get in a room with a doctor. We are going to see how we can push that information forward even when folks have limited cell phone coverage or broadband resources. Perhaps a nurse, a small lab and an X-ray machine can help make essential decisions before they start driving the patient 200 miles to the nearest hospital.

How does your team at Sanford define a health care desert? What does that mean in practice?

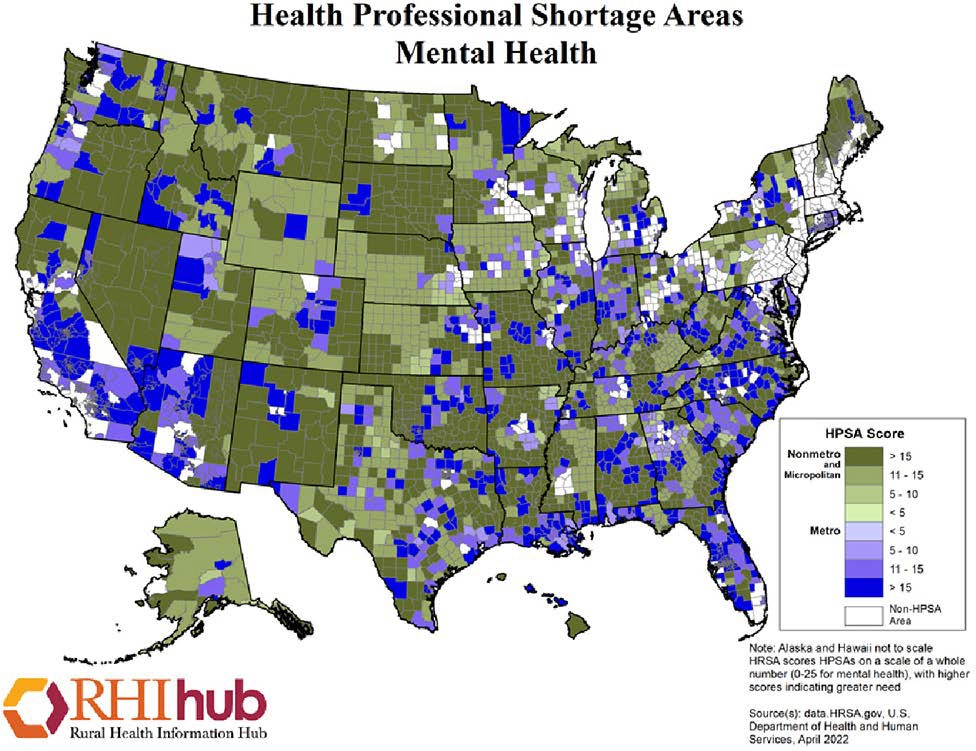

Much of that definition is based on the density of providers. For instance, we estimate that 91 percent of the counties that we serve have no mental health provider whatsoever.

I can tell you where the mental health providers are in Fargo. I can tell you where they are in Bismarck and Sioux Falls. But we recently had a case where a child urgently needed to see an adolescent psychiatrist. Because they live 250 miles from Fargo, the expected wait time was roughly six weeks.

With teenagers facing mental health issues, crises are more acute and need to be addressed in days, not weeks. With this in mind, we converted a time-intensive process into an efficient video visit with the appropriate adolescent psychiatrist within a week. The patient and the doctor talked and had a meaningful conversation in one- tenth of the time. Without telehealth the family routine would have been disrupted, the parents would have had to take time off work and spend hours driving to and from Fargo.

As of July 1, 2022, 60.24 percent of mental health professional shortage areas were located in rural areas. The April 2022 map above highlights mental health professional shortage areas for metro areas in multiple shades of purple and nonmetro areas in various shades of green. (Credit: Rural Health Information Hub)

We have discovered that there are many ways to interact with patients. Our mental health providers have really taken center stage in saying: We can connect with people who do not have the resources to drive or get to us. Whether or not you live in an inner city and you have 30 blocks to go, or you live in the country and you have 30 miles to go, that distance may be relatively similar for somebody with an anxiety disorder or depression. So making those connections through phone or video visits is powerful and essential.

“For us, it has been moving from: ‘The doctor will see you now,’ to ‘The patient will see you now.’”

It is important to think through how we make this adjustment and help the patient have that interaction in a way that does not require them to come across the street or the state.

What are the major health issues facing communities in rural America? Do these differ from issues in urban areas?

If you compare health issues in rural America to those in urban America, the diseases are the same. Diabetes is still diabetes; heart disease is still heart disease. Whether you live in South Dakota or New York City, finding a cheeseburger and a pack of cigarettes is not difficult. Finding health care is probably harder than finding both of those things.

So the health problems that we see are not that different. What is different is that because of some of the stoic mentalities of the folks that we work with, we do tend to see issues present a little bit later.

As we roll through summer right now, farmers are not interested in going to their doctor’s office. They are interested in making sure their crops are growing appropriately and their livestock are healthy. Farmers are working some of their longest and hardest hours right now, which means they are going to delay care unless it is some sort of emergency.

That has also been a big difficulty during the pandemic, because people who normally would have sought medical attention sooner are coming in six or 12 months later than they would have previously. Encouraging people to not delay and get care promptly is very important.

From a bedside manner perspective, how can health providers better communicate with patients in rural settings?

First off, everyone is more comfortable with providers they see on a regular basis. In many of these communities, the person who sees you for your health care may also have a kid on your child’s basketball team. That extra connection is very helpful, but, at the same time, everybody knows your business in a small town.

We need to support those connections and make sure that patients know that providers are there to improve their health and well-being, while allowing them to feel comfortable to speak freely.

Are there any sectors of medicine where telehealth and a virtual approach appear to work optimally?

Virtual visits with obstetricians have become a big win for us, helping to reduce the number of people traveling to our facilities by 50 percent in any given week. Virtual behavioral health visits have also been successful.

Even now, as in-person services resume at this stage of the pandemic, some of our behavioral health providers are still doing 75 to 80 percent of their consults virtually. It is better for a patient with an anxiety disorder or depression to be able to meet them where they are.

Dr. Jeremy Cauwels conducting a telehealth appointment

With video communication, our doctors can get a window into their homes and into their lives, too. It turns out that the background of your picture may be just as important as the person in front of it. Understanding that background helps our doctors understand whether a patient is coping well with their anxiety or mental health difficulties. It is more difficult to see that when somebody comes in dressed appropriately for their office visit compared to when you can see where and how they really live.

One of the other things we have rolled out is home monitoring. How do we care for a patient who is probably not sick enough to be in the hospital but, without medical intervention, is at an extraordinarily high risk of getting there? So, we can monitor them at home using a specially trained team of nurses who know when to call the doctor or intervene more aggressively.

One of the devices we use for that is called TytoCareTM. The device allows the patient to conduct a physical examination in their own home, which has tremendous benefits. We have been piloting that in various situations, including the care of children for those busy parents for whom an in-person visit would be difficult. We have used it for patients with chronic diseases such as heart failure or obstructive pulmonary disease who have recurrent visits. Why not do those from home?

We know what the problem is likely going to be, and all we have to do is recognize when it does not look like it is supposed to. In addition to telestroke services, there are virtual consults as well. You can sit in your local emergency room two and a half hours from Sanford’s major medical centers, and we can virtually bring you the specialists you need to see. So if you are concerned that this is an orthopedic injury, why not show the orthopedist a video or a live link of a doctor or a health care provider moving a patient through an exam before you assign them an appointment? You may very well be able to solve the problem right there.

That is a basic laundry list of the things that we can do to connect people in a way that keeps them closer to where they live and yet allows us to continue to provide them the best care possible from a place that previously was not an option.

Has your team encountered any barriers to care and how are you overcoming them?

In South Dakota, we have three of the top five poorest counties in the country. We also have six of the top 10 when you think of our bigger footprint. When you do that, you automatically have to assume that people are not going to have broadband internet connections or a smartphone in some of those counties and communities. They may not have any of the connectivity that you and I depend on in everyday life.

So how do you make better inroads for those folks to get connected? One of the things we talked about with those Main Street clinics is to bring that connectivity closer, so now they only have to drive into town as opposed to driving to Sioux Falls.

Those are the limitations that are the hardest to overcome—identifying the people who have fewer resources or limited ability. My parents are in their 70s, and although they are pretty good with technology I reset their Netflix every time I visit them. So the ability to solve problems if the interface is not perfectly user-friendly has to be another thing to consider when you are trying to reach people.

What is Sanford Health’s ultimate vision for rural health care? How do you measure success and what progress has been made so far?

We cover 250,000 square miles.

“The ultimate vision is to bring care as close to each individual patient as we possibly can, when they need it, not on our schedule.”

The other factor is that we have had the benefit of a benefactor who has been willing to support us as we roll forward. So we have had the financial opportunity to imagine how we might do things in the future that we don’t do today.

Currently, we are setting up smaller clinics that do not have a doctor physically present. We are also building a virtual care center, which is a brick-and- mortar facility where we can teach new providers and physicians how to do this work and cultivate a “webside manner” rather than a bedside manner.

It takes time for doctors to excel on screens, and it’s crucial to practice and invest in effective virtually focused teaching. Through our residency programs, we are also going to double the number

of residents and fellows that we have over the next decade. We want to make sure that they understand that communicating directly with their patients is not always going to be in a hospital room. We have to ask: What can you learn from these interactions screen-to-screen rather than face-to-face?

A digital rendering of Sanford Health’s new virtual care center

The virtual care center both helps us train new doctors who are ready for this challenge as well as puts us on the cutting-edge of how to make connections to provide care more efficiently, more accurately and in a way that is more user-friendly for our patients.

That is where health care needs to go in the future. And it is where we are hoping to lead the way in this rural space—finding a way to make it as easy as possible for as many people to see their doctor in the way that is most comfortable.

Have you run into any challenges in teaching the older generation of health providers to adopt telehealth?

During more intense periods of the pandemic, we had many clinicians adopting more video visits, including veteran providers. The questions are: Where did we turn it into a habit and a continuously useful tool? And where did people just go back to the way they always had done it before?

Older generations clearly wanted to see improvements in efficiency, lifestyle, patient care or other benefits that would convince them that they needed to adjust their previous approach. Many of our younger physicians are comfortable moving in digital spaces, so they have been willing to make the jump more quickly.

We have endocrinologists in our system who have converted either entire days or multiple half days of their clinic into digital work. When they sit down, they can review data more efficiently. If a patient has diabetes, the providers can see their blood sugars. If it is a thyroid problem, they can review the thyroid test. Physicians can make those connections, figure out what their plan is and connect to the patients digitally in a way that is just as fast and efficient, if not more, than bringing them into the office.

Dr. Jeremy Cauwels, chief physician at Sanford Health, harnesses his personal experiences to improve care for patients no matter their zip code

How might Sanford Health’s virtual care model be replicated in other areas with limited access or resources across the United States and abroad?

Right now, the goal is to get care across our target area. But there are people in our world clinics, in places like Ghana and Costa Rica, who are no closer to a neurologist locally than they are to our neurologist in Sioux Falls. So how do you bring a high level of expertise to places all over the world?

Maybe that is a step down the road for us, but it turns out the connection is exactly the same. From a digital standpoint, if we can get it done in one of the poorest counties in South Dakota, we can get it done in Costa Rica.

As we are looking at different places, we ask: How do we deliver the best care wherever we are called or however we are asked to help?

This interview has been edited for length and clarity.

If you have any questions or feedback, please contact: curalink@thecurafoundation.com

Newsletter created by health and science reporter and consulting producer for the Cura Foundation, Ali Pattillo, and associate director at the Cura Foundation, Svetlana Izrailova.