Our latest CuraLink conversation features one of the most influential leaders in health care in the United States: FDA Commissioner Dr. Robert Califf. Dr. Califf has a unique perspective with over 40 years of experience in cardiology, clinical research, academia, government and industry.

According to Dr. Califf, the biggest problem in medicine isn’t strictly medical, it’s social and political: misinformation. In the interview, Dr. Califf shares the central principles that guide his decision making, the challenges and opportunities facing the FDA and his hopes for the future of health innovation and well-being in the United States.

A conversation with Dr. Robert Califf

As the 25th United States’ Commissioner of Food and Drugs, Dr. Robert Califf leads the organization that is responsible for regulating nearly 20 percent of the country’s economy while promoting and protecting the public’s well-being. In an environment rife with misinformation, making and communicating regulatory decisions is arguably more challenging than ever.

Such a position of leadership might be daunting to most, but his decades working as a physician, researcher and industry leader have prepared him for the task. This vast experience has sharpened Dr. Califf’s ability to navigate complex issues like managing the recent infant formula shortage or regulating controversial practices like vaping.

Six months into his second tenure leading the agency, Dr. Califf shares how he follows his internal compass amid competing interests, ways to better communicate the nature of science, as well as his overarching vision for health care in the United States.

Ultimately, Dr. Califf tells the Cura Foundation, there is significant potential at this moment, but also “so much at risk.” Read on to hear how the Commissioner plans to use his influence at the FDA to maximize the health of all Americans.

Robert M. Califf, MD, 25th Commissioner of Food and Drugs, U.S. Food and Drug Administration

How is your vast background in academia, industry and policy influencing your second tenure as the FDA Commissioner?

It has been very helpful in trying to get the job done. Having experience in all of these sectors gives me a perspective that I would not otherwise have. It lets me know what is possible, because I have a sense of what all the different players can do. But it also lets me know what is not practical, because I see how others might look at a particular guidance, rule or decision.

How does your experience as an FDA Commissioner during the Obama administration inform your current approach and goals in the Biden administration? How has the role evolved?

Of course, the FDA Commissioner job exists within the executive branch of the government, so it always differs depending on the administration. There is no question that the political divide is much more profound than

it was in 2015 and 2016. It is a much rougher time in Washington. And that makes the job harder—there is no question about it.

I would also point out that technology has changed significantly in the past five to six years. There are many possibilities and realities right now that are multidimensional and much more complicated to deal with.

On the other hand, some things are the same. For example, the briefing I received on cannabis this past winter was almost exactly the same as the one I reviewed in 2016. There has been a lot more research, so the knowledge base is greater, but critical regulatory decisions are yet to be made.

Regulatory decisions for complex issues with no societal consensus, like cannabis, are difficult to make. In response, the can often gets kicked down the road instead of making decisions and moving forward.

Looking forward, what do you hope to accomplish during your tenure?

Well, I am 70 years old. I had not planned on coming back. When the call came to see if I would do it, the main consideration was: Can I make a difference?

I do think that, because of these politically charged times, it is good to be someone who is not going to be looking for their next job. Because no matter what you do, there is going to be hostility and negative things will be said about you.

“My main goal is to turn over the FDA in better shape with the next generation in mind.”

I have kids and grandkids, and I want the best for them. There is so much potential, but also so much at risk.

I would really stress that the FDA is both a regulatory agency and a public health agency, operating on a base of biomedical and engineering science. We are working at an unusual time in American history where life expectancy is going in the wrong direction. And although the FDA is only part of the overall picture, we have to be “in the arena,” to cite a Teddy Roosevelt speech, trying to fix it.

Robert M. Califf, MD, being sworn in as the 25th Commissioner of Food and Drugs, U.S. Food and Drug Administration

Do you have a guiding philosophy for your decision making at the agency and is it different the second time around?

In terms of principles, there are really two that guide me. Number one is my internal compass. It is very easy to lose your way in a job like this because the pressures are so intense. People are constantly trying to convince you to do things for a variety of reasons—usually good ones in their minds. Look at an issue like vaping, for example. There are very strong opinions on all sides, and yet you have to make decisions. Having an internal compass is critical.

The second guiding principle is public health. The question is: What set of decisions and approaches is going to lead to the best outcomes for the American people? That is our clarifying mission at the FDA.

Six months in, what have been the most critical issues you have faced, and how are you addressing them?

Well, one thing you learn to do in this type of job is to call anything your top priority depending on the audience. So there are many critical foci. As commissioner, you are regulating 20 percent of the United States’ economy, so you cannot be on point for every issue. For each item, there is someone else who is directly accountable.

With that in mind, my most pressing concern is misinformation. It does not matter whether it’s food, tobacco, drugs, devices or vaccines—we are in a different world of communication now.

Life expectancy is going backward in the U.S., and it is not a mystery what is causing death and disability. But

something is leading people to make adverse choices regarding their health, despite the amazing technology we have access to. Even though the U.S. is far and away the most potent source of new technology and biomedical breakthroughs, it seems that the rest of the world is better at figuring out how to use it. We now have a full five- year-shorter life span than other high-income countries.

The problem of people filling the internet, chat rooms and other spaces with information that is misleading or incorrect is far and away the biggest issue that we are facing.

With social media and seemingly infinite sources, how do you address misinformation?

If you have an answer, let me know because I have spoken to all of the world’s experts on the problem, both inside and outside of the U.S. government, and I have not yet found anyone who has a solution that is guaranteed to work.

There is an old saying: A lie goes around the world before the truth gets out of bed. It is empirically documented that this is the case. False information spreads about six times faster than the truth.

Of course, there is a lot we do differently day-to-day. Traditionally, the FDA has relied on its authority, in the case of health care, to put out a statement and have people trust it and promulgate it through doctors, nurses and pharmacists. On the food side, industry would promulgate that knowledge and information. But now it is quite different. If the minute a decision is made, there is information coming from all kinds of sources, we have to be much more proactive and preemptive, much like we would like to be about precision medicine when it comes to health care delivery.

We are not winning the battle right now. This is something that we need to really work on.

Going forward, how can the FDA keep pace with scientific innovation and the urgent need for new drugs and devices, while mitigating possible risks to consumers?

First of all, the FDA is made up of over 19,000 people. So job number one is to recruit and retain good people.

With our mission at the forefront, it is a very rewarding place to work. But as you might also imagine, given the length of the pandemic and the need for other issues across our portfolio to be addressed simultaneously, it has been very stressful. And although I am a fan of hybrid work environments, that adds another dynamic. It has been mostly virtual at the FDA. We are gradually coming back in a hybrid fashion, but the fact that we are not face-to- face with people means the camaraderie is not the same. Having said that, the productivity of our workforce has been unparalleled and the hybrid work environment is popular as opposed to full-time in the office.

The changes in the technology underpinning the industries we regulate are profound. On the one hand, it is exciting and gives us a reason to come to work. On the other hand, it adds to the complexity of the work and carries risks that mistakes will be made.

For example, we were talking this morning about robotic surgery. Imagine a child suffering a traumatic accident in a small town. With robotic surgery, you could have trauma surgeons scrub in virtually. But the number of steps to assemble multiple devices all within one platform, and the information technology to regulate it to ensure it is functioning correctly, is a monumental task. With this type of technology, mistakes could be made, but if you get it right, it will be incredibly rewarding.

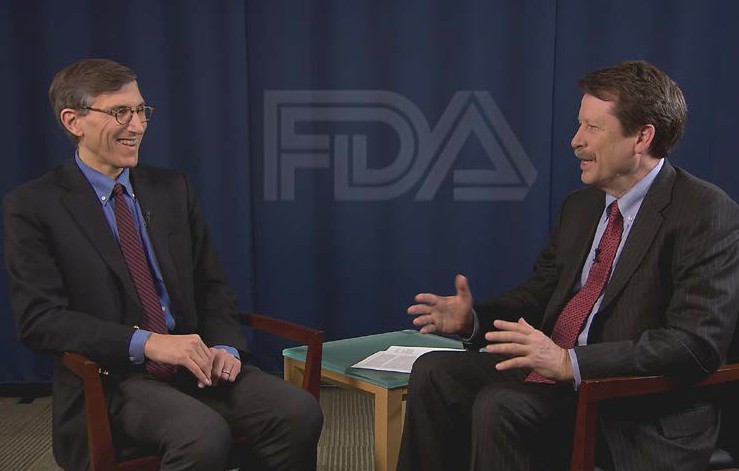

FDA Commissioner Califf with his team

Then, if we look at why our life expectancy is going backward, it is mostly due to common chronic diseases. We have multiple treatments for these that are already generic and inexpensive, but we are just not using them well as evidenced by our life expectancy deficit compared with our economic peer countries. We have to address these operational problems.

People do not often think that the FDA is responsible for food labels. Food has been a big focus in the midst of this epidemic of obesity and diabetes. Cancer is also a main focus of this administration, but most people do not even know that diabetes increases your risk of cancer approximately the same amount as it increases your risk of heart disease.

It is important to balance the excitement of new technology, which many of us love, with the need to focus on basic interventions and reinforce them and, ultimately, make it easier and more likely that people will do them.

With chronic diseases, do you predict that there will be a greater shift from focusing on treatment to focusing on prevention?

Balancing prevention and treatment approaches will be a challenge for us over the next few years. We have done a great job of rewarding and incentivizing the development of treatments for rare diseases and cancer. We should keep that up.

Peter Marks, MD, PhD, director of the Center for Biologics Evaluation and Research (CBER) at the Food and Drug Administration (left) in discussion with Dr. Califf (right) in 2016

Now we have to figure out how to incentivize industry, technologists and universities to spend more time figuring out what to do about the major diseases that are causing the most deaths and disabilities. I cannot say that I have the answer for how to do that.

“If you incentivize everything, you are not incentivizing anything.”

On the other hand, we do not want to lose any ground with rare diseases and cancer. We still have thousands of rare diseases that are not treatable right now. Cancer is still one of the three major causes of death and disability. So there is a lot to work on there.

How might real-world evidence and artificial intelligence (AI) be utilized in the evaluation process for FDA approvals?

For the most part, artificial intelligence is already built into our everyday lives more than it is into medicine. Although if you look at how hospitals and clinics run now, AI is humming in the background. Most people do not think about it that way, but increasingly AI is used for appointment scheduling and supply chain management.

The analogy I love to use is when you leave work today, or if you are at home and want to go to the grocery store, you might get in your driver’s seat and start talking to your car. So when you talk about real-world evidence—in the sense of helping us with the logistics, the conduct of health care and staying healthy—I think it is going to be increasingly built-in, similar to your car. In fact, your car will actually become a health tool, because it will increasingly keep you from getting into accidents. It will detect when you are on your cell phone or when you are distracted.

For the electronic health record, artificial intelligence is already a primary source of data. And when we talk about real-world evidence, we should not lose sight of the fact that we can do randomized trials using electronic health records as the data sources. Randomization is one way to turn data into evidence.

Soon, we are going to be surrounded by an envelope of information and knowledge about our health that we did not have before. I was doing some of this in my previous life at the Duke University School of Medicine. If you have 10,000 people in your health care program and you want to know who you should pay attention to today, you can use AI to identify risk using all the data streaming in from people’s health care encounters and their data from home. As we get better and better at using electronic health records, we can obtain a risk calculation every day or every minute. It will inform us about people who are having trouble at home that we would not have otherwise seen until they happen to come into the clinic.

Monitoring blood pressure or heart rate remotely is going to become standard fare. It is probably better done at home in the real world, where most things actually happen. We only spend about 0.2 percent of our lives in a hospital or a clinic.

Might drug approvals and labels become narrower based on certain biomarkers for disease subpopulations rather than disease categories as a whole?

With biomarkers, the theories, so far, have exceeded the practical reality. But similarly, with drug discovery, over 90 percent of drugs that get into Phase I trials do not make it to market, because Mother Nature is much more complicated than our brains are capable of understanding. So we try things in clinical trials, and most of them do not work.

In a similar way, biomarkers that look great in theory, and may even delineate subsets of populations who do better or worse, may not actually give useful information for which treatments work and how significant the treatment effect is. Those are different types of biomarkers. As we learn, biomarkers are going to get better and better.

For example, think about the recent Sodium-glucose Cotransporter-2 (SGLT2) inhibitors being used in cardiovascular disease, which is my specialty. They seem to work in almost every population. When the evidence is broad for big diseases, that is great. When you do have a difference in treatment effect as a function of a biological or clinical characteristic, then a biomarker can distinguish people who could benefit from those who could not.

“My great hope is that labels will reflect the evidence, and that the evidence will be strong and conclusive.”

That is what the label should say. So I think we will probably go both ways—we’ll continue to find broadly beneficial therapies for the broad, common chronic diseases and targeted therapies for subpopulations, and it will be driven by the evidence.

How is the FDA navigating drugs and tests that received emergency approval that may not be applicable given the new COVID-19 variants?

Remember, under emergency use authorization, the known and potential benefits need to outweigh the known and potential risks. It is the reasonably likely thing; it is not the proven thing. Sometimes it is not going to pan out, even when it is reasonably likely. When that happens, we can revoke the emergency use authorization, which is within the FDA’s purview. That is pretty uncommon.

What we are seeing now with the COVID-19 variants, BA-1 and BA-5, is that there is likely an advantage to a bivalent vaccine that has specific immune coverage for new variants. So we are most likely going to see a change in the fall’s vaccination regimen. There was an advisory committee recently on that topic, and that was their recommendation. So we will see how it turns out in manufacturing. In an ideal world, we would update our guidelines based on the constantly evolving evidence. The FDA is a critical part of that.

That can make it difficult when it comes to communication, right? Because as situations change, it can appear sort of “wishy-washy,” but it is not. In fact, the agency is reacting to changing data.

Yes, I link that back to misinformation as much as anything, because the nature of science is that it evolves. We are going to know more tomorrow than we knew today, and that means our recommendations may change.

I think it is very easy for people who want to play the misinformation game to say: “Well, they did not know what they were doing.”

For the people who fall prey to that, we need to better communicate the nature of science.

We are dealing with a probabilistic world when it comes to therapeutics, which means that if there is an 80 percent chance that the treatment is highly effective, there is a 20 percent chance that it is not. We need to continue to work on public education and also work within our scientific community on how we communicate to the public. We may not have all the answers, but we have to try to figure it out.

Do you have a message for the American people?

We are living at an exciting time for medicine and health care. In order to take full advantage of this moment, we need to focus on separating the information that is reliable and accurate from the information which is unreliable and may be misleading us into habits that are detrimental to our health.

That is something we all need to work on together.

This interview took place prior to the FDA’s authorization of bivalent COVID-19 vaccines and has been edited for length and clarity.

If you have any questions or feedback, please contact: curalink@thecurafoundation.com

Newsletter created by health and science reporter and consulting producer for the Cura Foundation, Ali Pattillo, and associate director at the Cura Foundation, Svetlana Izrailova.