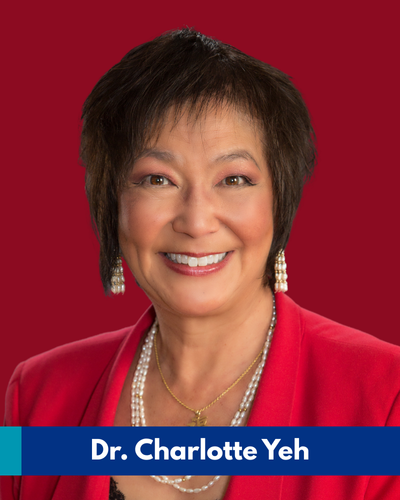

Recently, we spoke with Dr. Charlotte Yeh, an emergency medicine physician and chief medical officer of AARP Services, Inc., who is challenging how we perceive aging and older adults. According to Dr. Yeh, we mistakenly focus on all that is lost rather than what is gained with age. Wisdom and experience enable people to age gracefully to perfection. Together, we can challenge ageism and help bring dignity and purpose to each of us as we age.

Dr. Yeh thinks that older adults are the under-tapped engine of the economy as there are now over 1 billion people worldwide aged 60 years and over, a number predicted to grow to 1.4 billion by 2030 when the United Nations Decade of Healthy Ageing is set to end. We’re all aging, so let’s learn how to do it better.

A conversation with Dr. Charlotte Yeh

Aging is a biological inevitability that people go to great lengths to avoid. That’s because old age is perceived as a period of decline—our bodies often break down, minds cloud and social connections dwindle. But according to Dr. Charlotte Yeh, that negative perception doesn’t have to be a reality.

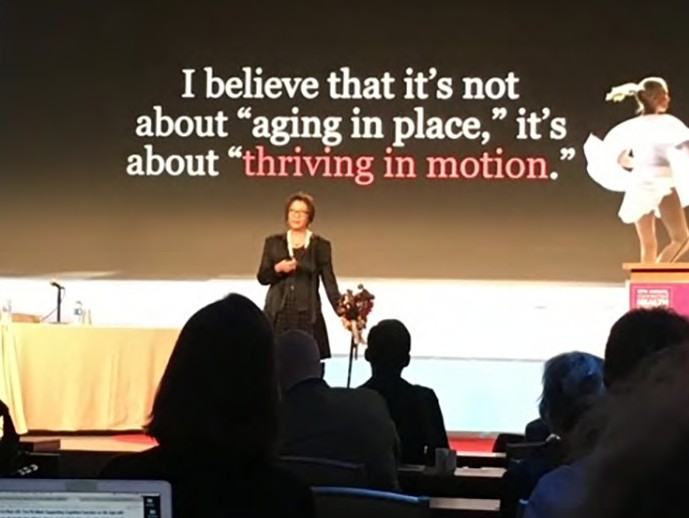

Getting older doesn’t automatically doom us to poor health or well-being. We can learn to “thrive in motion,” as Dr. Yeh puts it, rather than age in place.

At AARP, Dr. Yeh develops innovative health-related programs, initiatives and products to improve the lives of millions of older adults. Through groundbreaking innovation, new narratives around aging and more affordable care, life’s final chapter can be full of joy, not loss.

Why did you become a physician and specialize in emergency medicine?

I wanted to be a doctor since I was five and originally wanted to focus on research and do great experiments. But in medical school, I fell in love with patient care.

Although the only physician I knew growing up was a woman, there was still bias against women in medicine at that time. I first started in surgery, which was not common for women then. In residency interviews, I would hear things like: “Women cry and have babies.” or “We don’t hire women here.”

Charlotte Yeh, MD, Chief Medical Officer, AARP Services, Inc.

After my first few years in surgery, I realized that I loved every minute I spent in the emergency department. Surgery is action-oriented, but it takes time for people to heal and for providers to see results. In the emergency department, it was total chaos, and the results were immediate. And I loved making order out of chaos.

“Today the emergency department is the most egalitarian place in health care.”

But when I first started, this wasn’t true. If you didn’t have money, you were turned away. We fought for legislation so that no one missed out on critical care because of finances, lack of insurance or other factors when they had a true emergency. Whether you’re homeless or the president of the United States, you don’t get turned away from the ER.

Lastly, the emergency department is an incredible barometer of what does or doesn’t work in health care or the community. If something isn’t working, it comes through the ER doors. It helps to see where to focus energy inside and outside the hospital.

What made you interested in the health and well-being of older adults?

My interest was first ignited in the ER because we saw a preponderance of older adults and the great diversity in how they fared in crises. For example, we could have two 80-year-old women with similar broken hips. And I’d be able to confidently tell one: “You’re going to be fine. You’ll go home soon.” But I would know that the other patient wouldn’t walk out of the hospital.

Dr. Yeh (front row, in a flowered dress) was among several women in the first Emergency Medicine Residency class at UCLA

That diversity and complexity of how people age sparked my curiosity, and I started asking myself: “How can we create more of the first scenario and prevent the second?” and “Why don’t we support and replicate the thrivers instead of focusing on those who fail to thrive?”

The emergency department is an incredible window into family and social dynamics, too. Early in my career, I remember seeing a gentleman in his late 60s with repeated ER visits. He complained of shortness of breath, but after a massive workup, everything was negative. I took one look at him and said: “You look very sad.”

Dr. Yeh at 16 on the set of Mister Rogers’ Neighborhood showcasing what it’s like to be a female teenage scientist

He burst into tears. He had lost his partner of over 20 years two weeks earlier when his symptoms started. His real problem was loneliness. But being an older man, he couldn’t say: “I’m lonely.” He could only say: “I’m short of breath.” That’s when I understood how important social connections are.

I also saw how different caregiving experiences can be. Some older adults would be brought in with incredible, supportive and loving families, and you could easily recognize how such support can help them thrive. In other cases, you’d see caregivers who were so overwhelmed by life’s demands or the inability to handle stress that they couldn’t care for their loved ones and would leave them in the waiting room.

When you see those variations, you think that surely we can all do better for the older adults who are getting shortchanged along the way.

What is the most pressing health issue facing older adults today?

Given that health is a compilation of genetics, lifestyle, behavior, socialization, environment and attitudes, in the grand scheme of things, the most pressing issue is ageism. The fact that we don’t value aging in the U.S. really matters.

Ageism costs us an estimated $63 billion per year in health care. In our Medicare supplemental plan, about 40% of patients negatively view aging. That was associated with 33% higher healthcare costs. If you have a positive view of aging, you have a lower risk of hospitalization and a 44% higher chance of fully recovering from disability. You live seven and a half years longer, according to one study.

Ageism is so pervasive that about 93% of older adults say they’ve experienced it. It’s probably one of the few ‘isms’ that is still considered acceptable. The sad part is that a third of older adults have encountered it so much that they’ve internalized loneliness and depression as inevitable with aging.

Dr. Charlotte Yeh and other emergency department physicians with then-President Bill Clinton when they worked on health reform and critical care legislation

It’s all around us. You’re seven times more likely to have a negative marketing image if you’re over 50 than under. Seven out of 10 marketing images show people dependent, alone or in the home as opposed to being out in the community. Only 13% show an older adult in the workplace and 4% show them with a coworker, yet over a third of workers are 50 and older.

So if we want better health outcomes and lower costs of care, we have to change how we value aging and need to have a new narrative for aging. We all think of technology as a solution to health care. There was a UK study looking into how frequently digital health apps were prescribed across age groups. For patients under 35, it was 1 in 10 times; while it was 1 in 25 for patients over 50, and 1 in 50 for patients over 65. There is a perception that older adults don’t use technology. But 80% of older adults say they would love to try new technology.

What are the top health concerns for the elderly today?

AARP members have two major concerns: first, brain health. They want to maintain good cognition and not worry about dementia and Alzheimer’s. Second, they don’t want to be a burden on their families and children.

The Lancet Commission on dementia says that about 40% of dementia is avoidable, with the single biggest modifiable risk factor being hearing loss at 8%. Data suggests that over three years if people at risk for cognitive decline use hearing aids, 48% had mitigation of their cognitive decline.

So, if I could only fix one thing, it would be hearing loss. In your 60s, about a third of people have clinically significant hearing loss, and when you reach your 70s, the number rises to as many as two-thirds. This goes up with age. Hearing loss is associated with about $133 billion of lost productivity. Only 20 to 30% of people who need a hearing aid ever get it, and they typically wait eight to 10 years to get one. Medicare doesn’t cover hearing aids because hearing loss was considered “normal aging” in 1965 when the guidelines were established.

One of our studies shows that uncorrected hearing loss over 10 years was associated with 52% more dementia, 41% more depression, 29% more falls, 46% higher health care costs, 47% more hospitalization, an average of two and a half days longer hospital stay and 44% more readmission over 10 years.

Helen Keller said it best: “Blindness separates us from things, but deafness separates us from people.” This issue affects people’s quality of life, social networks, access to health care and communication and results in social isolation and loneliness. It’s very prevalent and impactful from health, economic and social perspectives.

Measurable and meaningful solutions exist. For people with hearing loss, we now have over-the-counter hearing aids and free captioning on phones, televisions and computers. We offer hearing tests on the AARP website and in person, free for AARP members.

What can we learn from other societies about aging and respecting and supporting the elderly?

Growing up in an Asian American family gave me a different viewpoint on aging. Asians tend to think in multifamily units, and there is a great respect for elders. Elders are regarded as wise, caring and knowledgeable. In the U.S., there’s more of an image of decline.

“We focus on what one loses with age but fail to talk about what is gained: wisdom, experience, better pattern recognition, improved problem-solving capabilities and more.”

In one study, researchers asked adults over 50 every five years if their health limited their ability to do work or housework. In their 50s, 89% said that they had no limitations. Even at 85 and up, 56% said they had no limitations. We think they would, but they don’t.

Another study on people 50 and older found that 78% of participants without a chronic condition were very optimistic. Even with a chronic condition, 56% were very optimistic about the future. 55% looked at retirement and said: “This is a new stage of life. This is not about decline or sliding into the sunset.”

“People believe that loneliness and depression are inevitable with aging, which isn’t true.”

As you age, you can actually be happier and have a reduced risk of depression and anxiety. I love the most recent Gallup study on happiness, which looked at 143 countries. The U.S. slipped overall from 15th to 23rd place, but Americans ranked higher or happier with age. The U.S. ranked low at 62 for people under 30. From 30 to 44 and from 45 to 64, the U.S. moved up to 42 and 17, respectively. But people over 60 ranked at number 10.

By the time people are in late life, they’ve had many challenges, built resilience, cultivated a sense of purpose and learned strategies for how to adapt. That’s not to say there isn’t loneliness. But we should support the assets of aging that help people thrive rather than bemoan the things they lose.

How does the global mental health crisis play out amongst the elderly?

It’s very heterogeneous. The most under-tapped area of opportunity is emotional well-being: cultivating people’s sense of resilience, social connection and purpose. I call it my three P’s: purpose, people and possibilities. When you have a strong sense of purpose and people to connect with, your sense of possibilities and optimism for tomorrow is endless. With purpose, people seek out more preventive services and have fewer hospitalizations.

Volunteerism, for example, is linked to better mental well-being, less depression and societal improvements. Data shows that if you exercise regularly, you can reduce your risk of hospitalization by 20%. But if you volunteer or help friends and family for two to four hours a week, your risk of hospitalization goes down by 27%. We have about 60,000 AARP volunteers across the country. One AARP Foundation program called Experience Corps shows that if you do something as simple as read to third graders, the kids end up having better careers, education and incomes. And it’s great for the volunteers, too.

AARP also launched Reach Out and Play last fall. We bring communities together to play board games across generations. Often, older adults come in moving slowly with their canes and walkers. During the game, they become more active, standing up, reaching across the table, giggling and laughing. The first trial last year was so successful that AARP is planning to sponsor a thousand events this year.

“Who says just because you’re older you can’t have fun, learn or play?”

We have failed to tap into social connection. Severe loneliness is associated with about 20% higher healthcare costs in our Medicare supplemental plan. We spend $6.7 billion in additional healthcare costs because of social isolation, which is the objective measure of loneliness.

AARP aims to create a more positive perception of aging. Our team worked with Allure magazine to drop the word ‘anti- aging’ in any of their advertising and copy. We worked with Getty Images to create thousands of new images that show active older adults—the way they are today.

In Singapore, there’s even a modeling agency for people aged 50 and older. We should be designing innovations with older adults in mind. Because if it works for an older adult, it’ll work for anybody, just like cut-outs in the sidewalk for people with wheelchairs that also help parents with strollers.

The U.S. is incredibly diverse—socioeconomically, ethnically and religiously—how does aging vary among different demographics and communities?

A good starting place is asking: “Can we start with what unifies us before we dig into what divides us?” and “Can we think of age as an equity issue?” Your religion, sexual orientation, race or ethnicity don’t matter. Everyone ages every minute of every day.

Our goal at AARP is to make sure that everybody can choose how they want to live and how they want to age. Giving people a sense of purpose cuts across socioeconomic status.

What is your ultimate vision for your work at AARP?

AARP focuses on three facets of consumers’ lives: health, wealth and self. Our goal is to help everyone live the life they want, no matter their age, age the way they want and be the best they can be. It may sound highfalutin or pollyannaish, but it’s real.

On top of that, how do we make health care more affordable, accessible and user-friendly? And in the broader community, how can we improve housing and transportation?

Based on the U.S. Department of Labor and Statistics, the only age group that will increase between now and 2030 in the workforce is 75 and older. How can we support a multi- generational workforce?

We know that we can’t solve all of people’s problems. On average, half of older adults will experience a major life change over two years: They may become a caregiver or an empty nester, lose a spouse/partner, get divorced, have a health issue or become unemployed. No one can take away

Dr. Charlotte Yeh is challenging preconceived notions of aging as a period of decline. Instead of focusing on what is lost, Dr. Yeh urges to focus on all that is gained—experience, wisdom and better pattern recognition

those challenges. But we can teach resilience and stress management. We can provide a sense of purpose and value, no matter the age. We can create opportunities for social connection. That emotional well-being that is so closely tied to our health, is also tied to our financial stability and sense of fulfillment. Then people can see that they can cope even if life’s not perfect. And in the process, we change the perception of aging.

How can U.S. health policy and financial structures better support aging people? If you could redesign Medicare, what would you change?

The first priority is reducing the fragmentation in health care. Behavioral health is separate from physical health, which is separate from cognitive health and social well-being. But these are all interconnected.

Second, three-quarters of older adults want to stay in their own homes, so how can we improve support at home? One of the biggest parts is caregiving. Right now, over 48 million caregivers devote $600 billion of unpaid labor to family caregiving. Six in 10 are doing medical procedures and activities they’re not trained for. On average, caregivers spend over $7,200 on out-of-pocket expenses on home renovations, health care and rent to keep their older loved ones at home.

There are some helpful initiatives. The Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services and Center for Medicare and Medicaid Innovation created a Dementia Guide to support caregivers on how to care for dementia, which is one of the more complex caregiving tasks. These organizations are recognizing that caregivers need respite care. Programs like Medicaid are now looking at paid family caregiving, which actually leads to lower overall healthcare costs. Learning how to embrace, support and acknowledge family caregivers would be huge in terms of the larger system.

There’s a trend toward moving the hospital into the home, which shifts more responsibility to caregivers. At innovation conferences, I hear many healthcare financiers say this is wonderful because it’s cheaper to provide care in the home. Nobody factors in the cost and impact on the family caregiver. If it becomes a burden, are there other lower-cost options to supply care?

We should provide care coordination and navigation and support for home renovations to build safety bars, stairs, ramps and doorways to improve accessibility for older adults. Ethel Percy Andrus founded AARP in 1958. In a presentation to President Eisenhower, she showed a model home that allowed older people to live better at home. There was an overhang so people didn’t get rained on at the front door. Electric sockets were placed three feet high, so people could reach them. Doorways were wide enough for wheelchairs. She did that back in the 1950s, and yet we’re still struggling today.

What are the top three recent research breakthroughs or emerging technologies that will reshape the lives of older people?

AARP invested in the Dementia Discovery Fund. When AARP first got involved, I thought it would be 30 years before we saw anything. Yet, in the last five years, we’ve already seen new drugs and therapies.

Maybe they’re not perfect yet. But remember when cancer was a word you never said. If you had it, you felt automatically doomed. That’s how we perceive dementia today. Yet new drugs and diagnostics are coming out that will change outlooks significantly.

Whether it’s Parkinson’s, dementia or motor impairments, I feel hopeful we will talk about cognitive change in the same way we now talk about cancer. With so many new treatments, we’re not doomed just because of a cancer diagnosis.

We’re learning more about the aging process itself. Whether it’s your brain, heart, muscles or bones, all organs age. Improving the understanding of basic biology can help further with issues like hearing loss and cognitive and heart decline.

If we reduce aging by one year, it could prevent an estimated $38 trillion in economic losses. From a technology perspective, that could happen in our lifetime. When I first started at AARP and would show up at technology and innovation

Dr. Yeh believes that aging should be about “thriving in motion” and not “aging in place.” We should enable people to “thrive physically, mentally, cognitively and spiritually,” she says conferences, the most common question I heard was: “What are you doing here?” Now, there’s recognition that people 50 and older make up the third largest economy in the world at $8.3 trillion. We spend $179 billion on our grandchildren and

$120 billion on technology. Aging is the growth engine for industry and technology going forward.

We’re already using virtual reality for memory care, sound and light for dementia and new caregiving platforms and tools for balance. There’s a big focus on independence in the home using remote monitoring and security measures. But even if the home is perfect and people can’t go outside, they aren’t happy.

“The real future for health as we age shouldn’t be focused on independence in the home but independence on the go.”

We should create technology that allows people to stay mobile, design more walkable parks and build livable communities that allow people to stay connected or bring the community into the home through technology.

What lessons did we learn during the pandemic that we need to carry forward?

One of the main lessons is that older people are not invisible. They are part of our families and societal fabric. The pandemic also reminded us that we need to embrace a new narrative of aging today and that we need to support care in the home.

What do you hope changes for older adults in the next generation?

I would like to see older adults be valued and have a sense of purpose. We know that age is just a number. But what’s important is: “How can we thrive as we age instead of becoming invisible?” and “How can we create more opportunities for older adults to feel valued?”

One great story illustrates how we can integrate older adults into communities. In France, an older lady lived by herself. Her neighbors were working parents, so every morning, they would drop their house keys off at her house and take their kids to school. Then, when the kids finished school, they walked to her house to pick up the keys. This may seem basic, but it’s really important.

The older woman got social interaction; she would make cookies and talk to the kids about their days. The parents were relieved because someone checked on their kids after school. Even though she was older, she became a critical resource and a hub in that community. People needed and valued her.

We have to help people thrive physically, mentally, cognitively and spiritually. Even if you’re stuck in a wheelchair, that doesn’t mean you can’t thrive in motion through your spirit. Let’s think of more opportunities to create that value. Let’s replace the term aging in place, which conjures images of being stuck, sitting in a chair and staring out the window. Instead, let’s thrive in motion.

That’s where I’d love to see us go.

This interview has been edited for length and clarity.

Newsletter created by health and science reporter and consulting producer for the Cura Foundation, Ali Pattillo, consulting editor, Catherine Tone and associate director at the Cura Foundation, Svetlana Izrailova.